sbt ハンドブック (日本語版草稿)

これは未だリリースされていない sbt 2.x のドキュメンテーションの草稿だ。一般的な概念は sbt 1.x とも一貫しているが、2.x 系および本稿の詳細は今後変更される可能性がある。

sbt は主に Scala と Java のためのシンプルなビルド・ツールだ。sbt は、Coursier を用いたライブラリ依存性のダウンロード、プロジェクトの差分コンパイルや差分テスト、IntelliJ や VS Code などの IDE との統合、JAR パッケージの作成、および JVM コミュニティーがパッケージ管理に用いる Central Repo への公開などを行う。

scalaVersion := "3.7.3"

Scala を始めるには、一行の build.sbt を書くだけでいい。

リンク

- 本稿のソースは sbt/website にて管理されている

- sbt 1.x のドキュメンテーション

sbt runner のインストール

sbt プロジェクトをビルドするためには、以下の手順をたどる必要がある:

- JDK をインストールする (Eclipse Adoptium Temurin JDK 8、11、17、もしくは ARM チップの macOS の場合、Zulu JDK を推奨)。

- sbt runner のインストール。

sbt runner は、宣言されたバージョンの sbt を必要に応じてダウンロードして、実行するスクリプトだ。この機構によってユーザのマシン環境に依存することなく、ビルド作者が sbt のバージョンを正確に管理することができる。

システム要件

sbt は主なオペレーティング・システムにおいて動作するが、事前に JDK 8 以上がインストールされていることを必要とする。

java -version

# openjdk version "1.8.0_352"

SDKMAN からのインストール

JDK と sbt のインストールをするのに、SDKMAN を使うことができる。

sdk install java $(sdk list java | grep -o "\b8\.[0-9]*\.[0-9]*\-tem" | head -1)

sdk install sbt

ユニバーサル・パッケージ

sbt runner の確認

sbt --script-version

# 1.12.0

例題でみる sbt

このページは、 sbt runner をインストールしたことを前提とする。

sbt の内部がどうなっているかや理由みたいなことを解説する代わりに、例題を次々と見ていこう。

最小 sbt ビルドを作る

mkdir foo-build

cd foo-build

touch build.sbt

mkdir project

echo "sbt.version=2.0.0-RC6" > project/build.properties

sbt シェルを起ち上げる

$ sbt

[info] welcome to sbt 2.0.0-RC6 (Azul Systems, Inc. Java)

....

[info] started sbt server

sbt:foo-build>

sbt シェルを終了させる

sbt シェルを終了させるには、exit と入力するか、Ctrl+D (Unix) か Ctrl+Z (Windows) を押す。

sbt:foo-build> exit

プロジェクトをコンパイルする

表記の慣例として sbt:...> や > というプロンプトは、sbt シェルに入っていることを意味することにする。

$ sbt

sbt:foo-build> compile

[success] elapsed time: 0 s, cache 0%, 1 onsite task

コード変更時に再コンパイルする

compile コマンド (やその他のコマンド) を ~ で始めると、プロジェクト内のソース・ファイルが変更されるたびにそのコマンドが自動的に再実行される。

sbt:foo-build> ~compile

[success] elapsed time: 0 s, cache 100%, 1 disk cache hit

[info] 1. Monitoring source files for foo-build/compile...

[info] Press <enter> to interrupt or '?' for more options.

ソース・ファイルを書く

上記のコマンドは走らせたままにする。別のシェルかファイルマネージャーからプロジェクトのディレクトリへ行って、src/main/scala/example というディレクトリを作る。次に好きなエディタを使って example ディレクトリ内に以下のファイルを作成する:

package example

@main def main(args: String*): Unit =

println(s"Hello ${args.mkString}")

この新しいファイルは実行中のコマンドが自動的に検知したはずだ:

[info] Build triggered by /tmp/foo-build/src/main/scala/example/Hello.scala. Running 'compile'.

[info] compiling 1 Scala source to /tmp/foo-build/target/out/jvm/scala-3.3.3/foo/backend ...

[success] elapsed time: 1 s, cache 0%, 1 onsite task

[info] 2. Monitoring source files for foo-build/compile...

[info] Press <enter> to interrupt or '?' for more options.

~compile を抜けるには Enter を押す。

以前のコマンドを実行する

sbt シェル内で上矢印キーを 2回押して、上で実行した compile コマンドを探す。

sbt:foo-build> compile

ヘルプを読む

help コマンドを使って、基礎コマンドの一覧を表示する。

sbt:foo-build> help

<command> (; <command>)* Runs the provided semicolon-separated commands.

about Displays basic information about sbt and the build.

tasks Lists the tasks defined for the current project.

settings Lists the settings defined for the current project.

reload (Re)loads the current project or changes to plugins project or returns from it.

new Creates a new sbt build.

new Creates a new sbt build.

projects Lists the names of available projects or temporarily adds/removes extra builds to the session.

....

特定のタスクの説明を表示させる:

sbt:foo-build> help run

Runs a main class, passing along arguments provided on the command line.

アプリを実行する

sbt:foo-build> run

[info] running example.main

Hello

[success] elapsed time: 0 s, cache 50%, 1 disk cache hit, 1 onsite task

sbt シェルから scalaVersion を設定する

sbt:foo-build> set scalaVersion := "3.7.3"

[info] Defining scalaVersion

[info] The new value will be used by Compile / bspBuildTarget, Compile / dependencyTreeCrossProjectId and 51 others.

[info] Run `last` for details.

[info] Reapplying settings...

[info] set current project to foo (in build file:/tmp/foo-build/)

scalaVersion セッティングを確認する:

sbt:foo-build> scalaVersion

[info] 3.7.3

セッションを build.sbt へと保存する

アドホックに設定したセッティングは session save で保存できる。

sbt:foo-build> session save

[info] Reapplying settings...

[info] set current project to foo-build (in build file:/tmp/foo-build/)

[warn] build source files have changed

[warn] modified files:

[warn] /tmp/foo-build/build.sbt

[warn] Apply these changes by running `reload`.

[warn] Automatically reload the build when source changes are detected by setting `Global / onChangedBuildSource := ReloadOnSourceChanges`.

[warn] Disable this warning by setting `Global / onChangedBuildSource := IgnoreSourceChanges`.

build.sbt ファイルは以下のようになったはずだ:

scalaVersion := "3.7.3"

プロジェクトに名前を付ける

エディタを使って、build.sbt を以下のように変更する:

scalaVersion := "3.3.3"

organization := "com.example"

name := "Hello"

ビルドの再読み込み

reload コマンドを使ってビルドを再読み込みする。このコマンドは build.sbt を読み直して、そこに書かれたセッティングを再適用する。

sbt:foo-build> reload

[info] welcome to sbt 2.x (Azul Systems, Inc. Java)

[info] loading project definition from /tmp/foo-build/project

[info] loading settings for project hello from build.sbt ...

[info] set current project to Hello (in build file:/tmp/foo-build/)

sbt:Hello>

プロンプトが sbt:Hello> に変わったことに注目してほしい。

libraryDependencies に toolkit-test を追加する

エディタを使って、build.sbt を以下のように変更する:

scalaVersion := "3.3.3"

organization := "com.example"

name := "Hello"

libraryDependencies += "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit-test" % "0.1.7" % Test

reload コマンドを使って、build.sbt の変更を反映させる。

sbt:Hello> reload

差分テストを実行する

sbt:Hello> test

差分テストを継続的に実行する

sbt:Hello> ~test

テストを書く

上のコマンドを走らせたままで、エディタから src/test/scala/example/HelloSuite.scala という名前のファイルを作成する:

package example

class HelloSuite extends munit.FunSuite:

test("Hello should start with H") {

assert("hello".startsWith("H"))

}

end HelloSuite

~test が検知したはずだ:

example.HelloSuite:

==> X example.HelloSuite.Hello should start with H 0.012s munit.FailException: /tmp/foo-build/src/test/scala/example/HelloSuite.scala:5 assertion failed

4: test("Hello should start with H") {

5: assert("hello".startsWith("H"))

6: }

at munit.FunSuite.assert(FunSuite.scala:11)

at example.HelloSuite.$init$$$anonfun$1(HelloSuite.scala:5)

[error] Failed: Total 1, Failed 1, Errors 0, Passed 0

[error] Failed tests:

[error] example.HelloSuite

[error] (Test / testQuick) sbt.TestsFailedException: Tests unsuccessful

[error] elapsed time: 1 s, cache 50%, 3 disk cache hits, 3 onsite tasks

テストが通るようにする

エディタを使って src/test/scala/example/HelloSuite.scala を以下のように変更する:

package example

class HelloSuite extends munit.FunSuite:

test("Hello should start with H") {

assert("Hello".startsWith("H"))

}

end HelloSuite

テストが通過したことを確認して、Enter を押して継続的テストを抜ける。

ライブラリ依存性を追加する

エディタを使って、build.sbt を以下のように変更する:

scalaVersion := "3.3.3"

organization := "com.example"

name := "Hello"

libraryDependencies ++= Seq(

"org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit" % "0.1.7",

"org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit-test" % "0.1.7" % Test,

)

reload コマンドを使って、build.sbt の変更を反映させる。

Scala REPL を使う

New York の現在の天気を調べてみる。

sbt:Hello> console

Welcome to Scala 3.3.3 (1.8.0_402, Java OpenJDK 64-Bit Server VM).

Type in expressions for evaluation. Or try :help.

scala>

import sttp.client4.quick.*

import sttp.client4.Response

val newYorkLatitude: Double = 40.7143

val newYorkLongitude: Double = -74.006

val response: Response[String] = quickRequest

.get(

uri"https://api.open-meteo.com/v1/forecast?latitude=\$newYorkLatitude&longitude=\$newYorkLongitude¤t_weather=true"

)

.send()

println(ujson.read(response.body).render(indent = 2))

// press Ctrl+D

// Exiting paste mode, now interpreting.

{

"latitude": 40.710335,

"longitude": -73.99307,

"generationtime_ms": 0.36704540252685547,

"utc_offset_seconds": 0,

"timezone": "GMT",

"timezone_abbreviation": "GMT",

"elevation": 51,

"current_weather": {

"temperature": 21.3,

"windspeed": 16.7,

"winddirection": 205,

"weathercode": 3,

"is_day": 1,

"time": "2023-08-04T10:00"

}

}

import sttp.client4.quick._

import sttp.client4.Response

val newYorkLatitude: Double = 40.7143

val newYorkLongitude: Double = -74.006

val response: sttp.client4.Response[String] = Response({"latitude":40.710335,"longitude":-73.99307,"generationtime_ms":0.36704540252685547,"utc_offset_seconds":0,"timezone":"GMT","timezone_abbreviation":"GMT","elevation":51.0,"current_weather":{"temperature":21.3,"windspeed":16.7,"winddirection":205.0,"weathercode":3,"is_day":1,"time":"2023-08-04T10:00"}},200,,List(:status: 200, content-encoding: deflate, content-type: application/json; charset=utf-8, date: Fri, 04 Aug 2023 10:09:11 GMT),List(),RequestMetadata(GET,https://api.open-meteo.com/v1/forecast?latitude=40.7143&longitude...

scala> :q // to quit

サブプロジェクトを作成する

build.sbt を以下のように変更する:

scalaVersion := "3.3.3"

organization := "com.example"

lazy val hello = project

.in(file("."))

.settings(

name := "Hello",

libraryDependencies ++= Seq(

"org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit" % "0.1.7",

"org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit-test" % "0.1.7" % Test

)

)

lazy val helloCore = project

.in(file("core"))

.settings(

name := "Hello Core"

)

reload コマンドを使って、build.sbt の変更を反映させる。

全てのサブプロジェクトを列挙する

sbt:Hello> projects

[info] In file:/tmp/foo-build/

[info] * hello

[info] helloCore

サブプロジェクトをコンパイルする

sbt:Hello> helloCore/compile

サブプロジェクトに toolkit-test を追加する

build.sbt を以下のように変更する:

scalaVersion := "3.3.3"

organization := "com.example"

val toolkitTest = "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit-test" % "0.1.7"

lazy val hello = project

.in(file("."))

.settings(

name := "Hello",

libraryDependencies ++= Seq(

"org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit" % "0.1.7",

toolkitTest % Test

)

)

lazy val helloCore = project

.in(file("core"))

.settings(

name := "Hello Core",

libraryDependencies += toolkitTest % Test

)

コマンドをブロードキャストする

hello に送ったコマンドを helloCore にもブロードキャストするために集約を設定する:

scalaVersion := "3.3.3"

organization := "com.example"

val toolkitTest = "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit-test" % "0.1.7"

lazy val hello = project

.in(file("."))

.aggregate(helloCore)

.settings(

name := "Hello",

libraryDependencies ++= Seq(

"org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit" % "0.1.7",

toolkitTest % Test

)

)

lazy val helloCore = project

.in(file("core"))

.settings(

name := "Hello Core",

libraryDependencies += toolkitTest % Test

)

reload 後、~test は両方のサブプロジェクトに作用する:

sbt:Hello> ~test

Enter を押して継続的テストを抜ける。

hello が helloCore に依存するようにする

サブプロジェクト間の依存関係を定義するには .dependsOn(...) を使う。ついでに、toolkit への依存性も helloCore に移そう。

scalaVersion := "3.3.3"

organization := "com.example"

val toolkitTest = "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit-test" % "0.1.7"

lazy val hello = project

.in(file("."))

.aggregate(helloCore)

.dependsOn(helloCore)

.settings(

name := "Hello",

libraryDependencies += toolkitTest % Test

)

lazy val helloCore = project

.in(file("core"))

.settings(

name := "Hello Core",

libraryDependencies += "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit" % "0.1.7",

libraryDependencies += toolkitTest % Test

)

uJson を使って JSON をパースする

helloCore に uJson を追加しよう。

core/src/main/scala/example/core/Weather.scala を追加する:

package example.core

import sttp.client4.quick._

import sttp.client4.Response

object Weather:

def temp() =

val response: Response[String] = quickRequest

.get(

uri"https://api.open-meteo.com/v1/forecast?latitude=40.7143&longitude=-74.006¤t_weather=true"

)

.send()

val json = ujson.read(response.body)

json.obj("current_weather")("temperature").num

end Weather

次に src/main/scala/example/Hello.scala を以下のように変更する:

package example

import example.core.Weather

@main def main(args: String*): Unit =

val temp = Weather.temp()

println(s"Hello! The current temperature in New York is $temp C.")

アプリを走らせてみて、うまくいったか確認する:

sbt:Hello> run

[info] compiling 1 Scala source to /tmp/foo-build/core/target/scala-2.13/classes ...

[info] compiling 1 Scala source to /tmp/foo-build/target/scala-2.13/classes ...

[info] running example.Hello

Hello! The current temperature in New York is 22.7 C.

一時的に scalaVersion を変更する

sbt:Hello> ++3.3.3!

[info] Forcing Scala version to 3.3.3 on all projects.

[info] Reapplying settings...

[info] Set current project to Hello (in build file:/tmp/foo-build/)

scalaVersion セッティングを確認する:

sbt:Hello> scalaVersion

[info] helloCore / scalaVersion

[info] 3.3.3

[info] scalaVersion

[info] 3.3.3

このセッティングは reload 後には無効となる。

バッチ・モード

sbt のコマンドをターミナルから直接渡して sbt をバッチモードで実行することができる。

$ sbt clean "testOnly HelloSuite"

sbt new コマンド

sbt new コマンドを使って手早く簡単な Hello world ビルドをセットアップすることができる。

$ sbt new scala/scala-seed.g8

....

A minimal Scala project.

name [My Something Project]: hello

Template applied in ./hello

プロジェクト名を入力するプロンプトが出てきたら hello と入力する。

これで、hello ディレクトリ以下に新しいプロジェクトができた。

クレジット

本ページは William “Scala William” Narmontas さん作の Essential sbt というチュートリアルに基づいて書かれた。

sbt 入門

sbt は、柔軟かつ強力なビルド定義を持つが、それを裏付けるいくつかの概念がある。それらの概念は数こそ多くはないが、sbt は他のビルドシステムとは少し違うので、ドキュメントを読まずに使おうとすると、きっと細かい点でつまづいてしまうだろう。

この sbt 入門ガイドでは、sbt ビルド定義を作成してメンテナンスしていく上で知っておくべき概念を説明していく。

このガイドを一通り読んでおくことを強く推奨したい。

sbt の存在理由

背景

Scala 3 Book に書かれてある通り、Scala においてライブラリやプログラムは Scala コンパイラ scalac によってコンパイルされる:

@main def hello() = println("Hello, World!")

$ scalac hello.scala

$ scala hello

Hello, World!

いちいち毎回 scalac に全ての Scala ソースファイル名を直接渡すのは面倒だし遅い。

さらに、例題的なプログラム以外のものを書こうとすると普通はライブラリ依存性を持つことになり、つまり間接的なライブラリ依存を持つことにもなる。Scala エコシステムは、Scala 2.12系、2.13系、3.x系、JVMプラットフォーム、 JSプラットフォーム、 Native プラットフォームなどがあるため二重、三重に複雑な問題だ。

JAR ファイルや scalac を直接用いるという代わりに、サブプロジェクトという抽象概念とビルドツールを導入することで、無意味に非効率的な苦労を回避することができる。

sbt

sbt は主に Scala と Java のためのシンプルなビルド・ツールだ。sbt を使うことで、サブプロジェクトおよびそれらの依存性、カスタム・タスクを宣言することができ、高速かつ再現性のあるビルドを得ることができる。

この目標のため、sbt はいくつかのことを行う:

- sbt 自身のバージョンは

project/build.propertiesにて指定される。 - build.sbt DSL という DSL (ドメイン特定言語) を定義し、

build.sbtにて Scala バージョンその他のサブプロジェクトに関する情報を宣言できるようにする。 - Cousier を用いてサブプロジェクトのライブラリ依存性や間接的依存性を取得する。

- Zinc を呼び出して Scala や Java ソースの差分コンパイルを行う。

- 可能な限り、タスクを並列実行する。

- JVM エコシステム全般と相互乗り入れが可能なように、パッケージが Maven リポジトリにどのように公開されるべきかの慣習を定義する。

sbt は、プログラムやライブラリのビルドに必要なコマンド実装の大部分を標準化していると言っても過言ではない。

build.sbt DSL の必要性

sbt はサブプロジェクトとタスクグラフを宣言するのに Scala 言語をベースとする build.sbt DSL を採用する。昨今では、YAML や XML といった設定形式の代わりに DSL を使っていることは sbt に限らない。Gradle、Google 由来の Bazel 、Meta の Buck、Apple の SwiftPM など多くのビルドツールが DSL を用いてサブプロジェクトを定義する。

build.sbt は、scalaVersion と libraryDependencies のみを宣言すればあたかも YAML ファイルのように始めることができるが、ビルドシステムへの要求が高度になってもスケールすることができる。

- ライブラリのためのバージョン番号など同じ情報の繰り返しを回避するため、

build.sbtはvalを使って変数を宣言できる。 - セッティングやタスクの定義内で必要に応じて

ifのような Scala 言語の言語構文を使うことができる。 - セッティングやタスクが静的型付けされているため、ビルドが始まる前にタイポミスや型の間違いなどをキャッチできる。型は、タスク間でのデータの受け渡しにも役立つ。

Initialized[Task[A]]を用いた構造的並行性を提供する。この DSL はいわゆる「直接スタイル」な.value構文を用いて簡潔にタスクグラフを定義することができる。- プラグインを通して sbt の機能を拡張して、カスタム・タスクや Scala.JS といった言語拡張を行うという強力な権限をコミュニティーに与えている。

新しいビルドの作成

新しいビルドを作成するには、sbt new を使う。

$ mkdir /tmp/foo

$ cd /tmp/foo

$ sbt new

Welcome to sbt new!

Here are some templates to get started:

a) scala/toolkit.local - Scala Toolkit (beta) by Scala Center and VirtusLab

b) typelevel/toolkit.local - Toolkit to start building Typelevel apps

c) sbt/cross-platform.local - A cross-JVM/JS/Native project

d) scala/scala3.g8 - Scala 3 seed template

e) scala/scala-seed.g8 - Scala 2 seed template

f) playframework/play-scala-seed.g8 - A Play project in Scala

g) playframework/play-java-seed.g8 - A Play project in Java

i) softwaremill/tapir.g8 - A tapir project using Netty

m) scala-js/vite.g8 - A Scala.JS + Vite project

n) holdenk/sparkProjectTemplate.g8 - A Scala Spark project

o) spotify/scio.g8 - A Scio project

p) disneystreaming/smithy4s.g8 - A Smithy4s project

q) quit

Select a template:

「a」を選択すると、いくつかの質問が追加で表示される:

Select a template: a

Scala version (default: 3.3.0):

Scala Toolkit version (default: 0.2.0):

リターンキーを押せば、デフォルト値が選択される。

[info] Updated file /private/tmp/bar/project/build.properties: set sbt.version to 1.9.8

[info] welcome to sbt 1.9.8 (Azul Systems, Inc. Java 1.8.0_352)

....

[info] set current project to bar (in build file:/private/tmp/foo/)

[info] sbt server started at local:///Users/eed3si9n/.sbt/1.0/server/d0ac1409c0117a949d47/sock

[info] started sbt server

sbt:bar> exit

[info] shutting down sbt server

以下はこのテンプレートによって作成されたファイルだ:

.

├── build.sbt

├── project

│ └── build.properties

├── src

│ ├── main

│ │ └── scala

│ │ └── example

│ │ └── Main.scala

│ └── test

│ └── scala

│ └── example

│ └── ExampleSuite.scala

└── target

build.sbt ファイルを見ていこう:

val toolkitV = "0.2.0"

val toolkit = "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit" % toolkitV

val toolkitTest = "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit-test" % toolkitV

scalaVersion := "3.3.0"

libraryDependencies += toolkit

libraryDependencies += (toolkitTest % Test)

これは、ビルド定義と呼ばれ、sbt がプロジェクトをコンパイルするのに必要な情報が記述されている。これは、.sbt 形式という Scala 言語のサブセットで書かれている。

以下は src/main/scala/example/Main.scala の内容だ:

package example

@main def main(args: String*): Unit =

println(s"Hello ${args.mkString}")

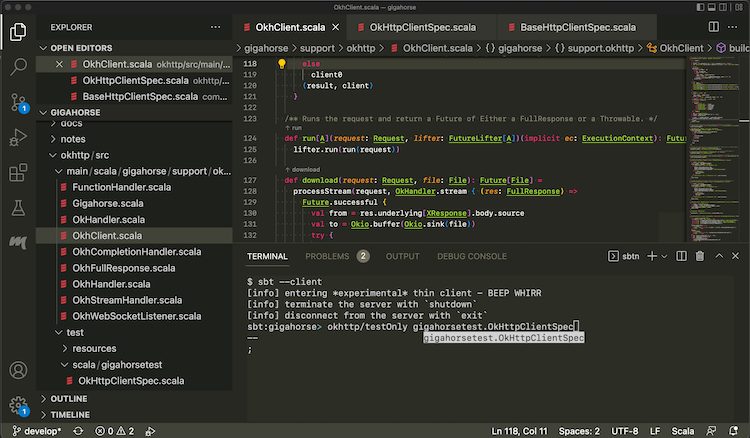

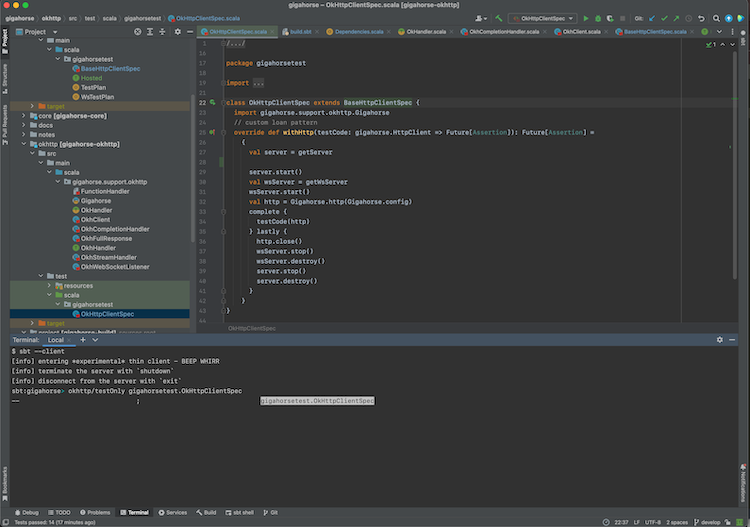

これは、Hello world のテンプレートだ。これを実行するには、sbt --client と打ち込んで sbt シェルを起動して、シェル内から run <名前> と入力する:

$ sbt --client

[info] entering *experimental* thin client - BEEP WHIRR

[info] server was not detected. starting an instance

....

info] terminate the server with `shutdown`

[info] disconnect from the server with `exit`

sbt:bar> run Raj

[info] running example.main Raj

Hello Raj

[success] Total time: 0 s, completed Feb 18, 2024 2:38:10 PM

Giter8 テンプレート

.local テンプレートもいくつかあるが、基本的に sbt new は Giter8 と統合して GitHub 上でホスティングされるテンプレートを開く。例えば、scala/scala3.g8 は Scala チームによりメンテナンスされ、新しい Scala 3 のビルドを作成する:

$ /tmp

$ sbt new scala/scala3.g8

Giter8 wiki では 100 以上のテンプレートが列挙されていて、新しいビルドを手早く作ることができる。

sbt のコンポーネント

sbt runner

sbt のビルドは、「sbt という名前のシェルスクリプト」によって実行され、このスクリプトは sbt runner と呼ばれる。

project/build.properties による sbt バージョンの指定

sbt runner は、そのサブコンポーネントである sbt launcher を実行し、sbt launcher は project/build.properties を読み込んで、そのビルドに使われる sbt のバージョンを決定し、キャッシュに無ければ sbt 本体をダウンロードする:

sbt.version=2.0.0-RC6

これは、つまり

- ビルドをチェックアウトした人が、各々の sbt runner のバージョンに関わらわず、同一の sbt のバージョンを実行し

- sbt 本体のバージョンは git のようなバージョン管理システムによって管理されることを意味する

sbtn (sbt --client)

sbtn (native thin client) は sbt runner のサブコンポーネントの一つで、sbt runner に --client フラグを渡すと呼ばれ、sbt server にコマンドを送信するのに使われる。名前に n が付いているのは、それが GraalVM native-image によってネーティブ・コードにコンパイルされていることに由来する。sbtn と sbt server は安定しているため、最近の sbt のバージョンなら大体動作するようになっている。

sbt server (sbt --server)

sbt server は、ビルドツール本体で、そのバージョンは project/build.properties によって指定される。sbt server は、sbtn やエディタから注文を受け取るレジ係の役割を持つ。

Coursier

sbt server は、そのサブコンポーネントとして Couriser を実行して、Scala 標準ライブラリ、Scala コンパイラ、ビルドで使われるその他のライブラリ依存性の解決を行う。

Zinc

Zinc は、sbt プロジェクトにより開発、メンテされている、Scala の差分コンパイラだ。Zinc の側面として見落とされがちなのは、Zinc はここ数年に出た全てのバージョンの Scala コンパイラに対する安定した API を提供しているということがある。Coursier がどんな Scala バージョンでも解決できることと合わせると、sbt は build.sbt に一行書くだけで、ここ数年に出たどのバージョンの Scala でも走らせることができる:

scalaVersion := "3.7.3"

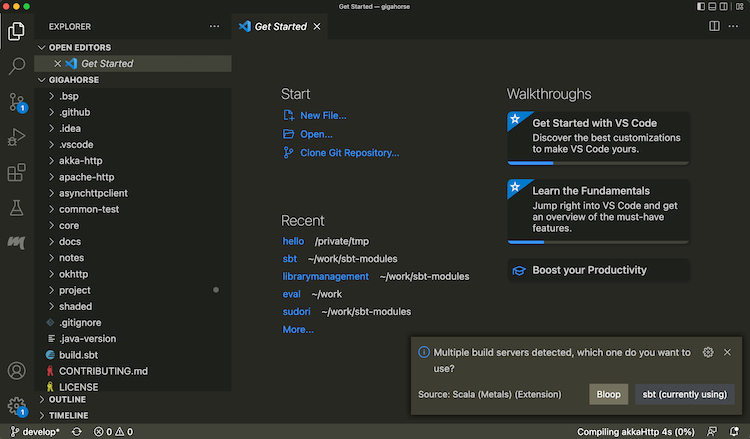

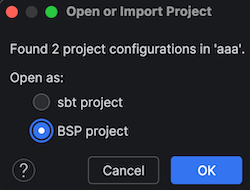

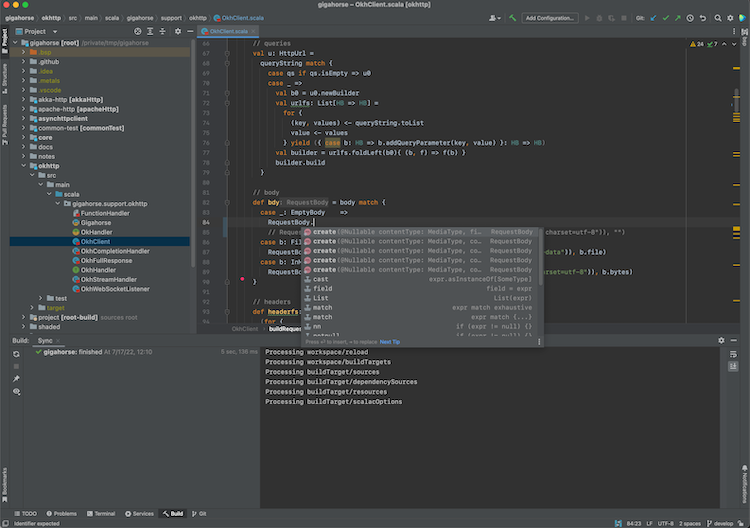

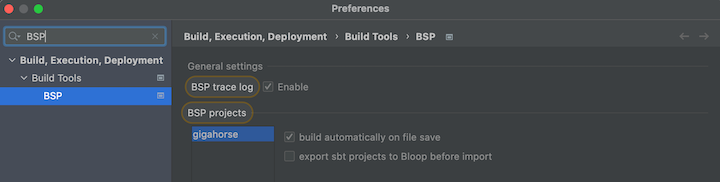

BSP server

sbt server は Build Server Protocol (BSP) をサポートして、ビルド対象の列挙、ビルドの実行、その他を行うことができる。これにより、IntelliJ や Metals といった IDE が既に実行中の sbt server とコードを用いて通信することが可能となる。

sbt server との接続

sbt server との接続方法を 3通りみていく。

sbtn を用いた sbt シェル

ビルドのワーキング・ディレクトリ内で sbt を実行する:

sbt

これは以下のように表示されるはずだ:

$ sbt

[info] server was not detected. starting an instance

[info] welcome to sbt 2.0.0-alpha7 (Azul Systems, Inc. Java 1.8.0_352)

[info] loading project definition from /private/tmp/bar/project

[info] loading settings for project bar from build.sbt ...

[info] set current project to bar (in build file:/private/tmp/bar/)

[info] sbt server started at local:///Users/eed3si9n/.sbt/2.0.0-alpha7/server/d0ac1409c0117a949d47/sock

[info] started sbt server

[info] terminate the server with `shutdown`

[info] disconnect from the server with `exit`

sbt:bar>

sbt をコマンドラインの引数無しで実行すると、sbt シェルが起動する。sbt シェルは、コマンド打ち込むためのプロンプトを持つが、タブ補完が効き、履歴も持っている。

例えば、sbt シェルに compile と打ち込むことができる:

sbt:bar> compile

compile を再実行するには、上矢印を押下して、リターンキーを押す。

sbt シェルを中止するには、exit と打ち込むか、 Ctrl-D (Unix) もしくは Ctrl-Z (Windows) を使う。

sbtn を用いたバッチ・モード

sbt をバッチ・モードで使うことも可能だ:

sbt compile

sbt testOnly TestA

$ sbt compile

> compile

sbt server のシャットダウン

マシン上の sbt server を全てシャットダウンするには以下を実行する:

sbt shutdownall

現行のものだけをシャットダウンするには以下を実行する:

sbt shutdown

基本タスク

このページは sbt をセットアップした後の、基本的な使い方を解説する。このページは、sbt のコンポーネントを既に読んだことを前提とする。

sbt を使っているリポジトリを pull してきたら、手軽に使ってみることができる。まずは、GitHub などから、リポジトリを選んでチェックアウトする。

$ git clone https://github.com/scalanlp/breeze.git

$ cd breeze

sbtn を用いた sbt シェル

sbt のコンポーネント でも言及されたように、sbt シェルを起動する:

$ sbt

これは以下のように表示されるはずだ:

$ sbt

[info] entering *experimental* thin client - BEEP WHIRR

[info] server was not detected. starting an instance

[info] welcome to sbt 1.5.5 (Azul Systems, Inc. Java 1.8.0_352)

[info] loading global plugins from /Users/eed3si9n/.sbt/1.0/plugins

[info] loading settings for project breeze-build from plugins.sbt ...

[info] loading project definition from /private/tmp/breeze/project

Downloading https://repo1.maven.org/maven2/org/scalanlp/sbt-breeze-expand-codegen_2.12_1.0/0.2.1/sbt-breeze-expand-codegen-0.2.1.pom

....

[info] sbt server started at local:///Users/eed3si9n/.sbt/1.0/server/dd982e07e85c7de1b618/sock

[info] terminate the server with `shutdown`

[info] disconnect from the server with `exit`

sbt:breeze-parent>

projects コマンド

まずは手始めに、projects コマンドを使ってサブプロジェクトを列挙してみる:

sbt:breeze-parent> projects

[info] In file:/private/tmp/breeze/

[info] benchmark

[info] macros

[info] math

[info] natives

[info] * root

[info] viz

現行のサプブロジェクト root を含み、合計 6つのをサブプロジェクトを持つビルドであることが分かる。

tasks コマンド

同様に、tasks コマンドを用いて、このビルドが持つ全タスクを列挙することができる:

sbt:breeze-parent> tasks

This is a list of tasks defined for the current project.

It does not list the scopes the tasks are defined in; use the 'inspect' command for that.

Tasks produce values. Use the 'show' command to run the task and print the resulting value.

bgRun Start an application's default main class as a background job

bgRunMain Start a provided main class as a background job

clean Deletes files produced by the build, such as generated sources, compiled classes, and task caches.

compile Compiles sources.

console Starts the Scala interpreter with the project classes on the classpath.

consoleProject Starts the Scala interpreter with the sbt and the build definition on the classpath and useful imports.

consoleQuick Starts the Scala interpreter with the project dependencies on the classpath.

copyResources Copies resources to the output directory.

doc Generates API documentation.

package Produces the main artifact, such as a binary jar. This is typically an alias for the task that actually does the packaging.

packageBin Produces a main artifact, such as a binary jar.

packageDoc Produces a documentation artifact, such as a jar containing API documentation.

packageSrc Produces a source artifact, such as a jar containing sources and resources.

publish Publishes artifacts to a repository.

publishLocal Publishes artifacts to the local Ivy repository.

publishM2 Publishes artifacts to the local Maven repository.

run Runs a main class, passing along arguments provided on the command line.

runMain Runs the main class selected by the first argument, passing the remaining arguments to the main method.

test Executes all tests.

testOnly Executes the tests provided as arguments or all tests if no arguments are provided.

testQuick Executes the tests that either failed before, were not run or whose transitive dependencies changed, among those provided as arguments.

update Resolves and optionally retrieves dependencies, producing a report.

More tasks may be viewed by increasing verbosity. See 'help tasks'

compile

compile タスクは、ライブラリ依存性の解決とダウンロードを行った後に、ソースのコンパイルを行う。

> compile

これは以下のように表示されるはずだ:

sbt:breeze-parent> compile

[info] compiling 341 Scala sources and 1 Java source to /private/tmp/breeze/math/target/scala-3.1.3/classes ...

| => math / Compile / compileIncremental 51s

run

run タスクは、サブプロジェクトのメインクラスを実行する。sbt シェルから math/run と打ち込む:

> math/run

math/run は、math サブプロジェクトにスコープ付けされた run タスクを意味する。これは、以下のように表示されるはずだ:

sbt:breeze-parent> math/run

[info] Scala version: 3.1.3 true

....

Multiple main classes detected. Select one to run:

[1] breeze.optimize.linear.NNLS

[2] breeze.optimize.proximal.NonlinearMinimizer

[3] breeze.optimize.proximal.QuadraticMinimizer

[4] breeze.util.UpdateSerializedObjects

Enter number:

プロンプトには 1 と入力する。

test

test タスクは、以前に失敗したテスト、未だ実行されていないテスト、及び間接的依存性に変化があったテストを実行する。

> math/test

これは以下のように表示されるはずだ:

sbt:breeze-parent> math/testQuick

[info] FeatureVectorTest:

[info] - axpy fv dv (1 second, 106 milliseconds)

[info] - axpy fv vb (9 milliseconds)

[info] - DM mult (19 milliseconds)

[info] - CSC mult (32 milliseconds)

[info] - DM trans mult (4 milliseconds)

....

[info] Run completed in 58 seconds, 183 milliseconds.

[info] Total number of tests run: 1285

[info] Suites: completed 168, aborted 0

[info] Tests: succeeded 1285, failed 0, canceled 0, ignored 0, pending 0

[info] All tests passed.

[success] Total time: 130 s (02:10), completed Feb 19, 2024

watch (チルダ) コマンド

編集-コンパイル-テストの一連のサイクルの高速化のために、ソースが保存されるたびに自動的に再コンパイルか再テストを行うように sbt に命令することができる。

コマンドの前に ~ を付けることで、ファイルが変更されるたびに自動的にそのコマンドが実行されるようになる。例えば、sbt シェルから以下のように打ち込む:

> ~test

リターンキーを押下して、監視を中止する。~ の前置記法は sbt シェルからもバッチ・モードからでも使用可能。

ビルド定義の基本

このページは build.sbt のビルド定義を解説する。

ビルド定義とは何か

ビルド定義は、build.sbt にて定義され、プロジェクト (型は Project) の集合によって構成される。 プロジェクトという用語が曖昧であることがあるため、このガイドではこれらをサブプロジェクトと呼ぶことが多い。

例えば、カレントディレクトリにあるサブプロジェクトは build.sbt に以下のように定義できる:

scalaVersion := "3.3.3"

name := "Hello"

より明示的に書くと:

lazy val root = (project in file("."))

.settings(

scalaVersion := "3.3.3",

name := "Hello",

)

それぞれのサブプロジェクトは、キーと値のペアによって詳細が設定される。例えば、name というキーがあるが、それはサブプロジェクト名という文字列の値に関連付けられる。キーと値のペア列は .settings(...) メソッド内に列挙される。

build.sbt DSL

build.sbt は、Scala に基づいた build.sbt DSL と呼ばれるドメイン特定言語 (DSL) を用いてサブプロジェクトを定義する。まずは scalaVersion と libraryDependencies のみを宣言して、YAML ファイルのように build.sbt を使うことができるが、ビルドの成長に応じてその他の機能を使ってビルド定義を整理することができる。

型付けされたセッティング式

build.sbt DSL をより詳しくみていこう:

organization := "com.example"

^^^^^^^^^^^^ ^^^^^^^^ ^^^^^^^^^^^^^

key operator (setting/task) body

それぞれのエントリーはセッティング式と呼ばれる。セッティング式にはタスク式と呼ばれるものもある。この違いは後で説明する。

セッティング式は以下の 3部から構成される:

- 左辺項をキー (key) という。

- 演算子。この場合は

:=。 - 右辺項は本文 (body)、もしくはセッティング本文という。

左辺値の name、version、および scalaVersion はキーである。 キーは SettingKey[A]、 TaskKey[A]、もしくは InputKey[A] のインスタンスで、 A はその値の型である。キーの種類に関しては後述する。

name キーは SettingKey[String] に型付けされているため、 name の := 演算子も String に型付けされている。これにより、誤った型の値を使おうとするとビルド定義はコンパイルエラーになる:

name := 42 // コンパイルできない

val と lazy val

ライブラリのバージョン番号など同じ情報の繰り返しを避けるために、build.sbt 内の任意の行に val、lazy val、def を書くことができる。

val toolkitV = "0.2.0"

val toolkit = "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit" % toolkitV

val toolkitTest = "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit-test" % toolkitV

scalaVersion := "3.7.3"

libraryDependencies += toolkit

libraryDependencies += (toolkitTest % Test)

上の例で val は変数を定義し、上の行から順に初期化される。そのため、toolkitV が参照される前に定義される必要がある。

以下は悪い例:

// 悪い例

val toolkit = "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit" % toolkitV // 未初期化の参照!

val toolkitTest = "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit-test" % toolkitV // 未初期化の参照!

val toolkitV = "0.2.0"

build.sbt に未初期化の事前参照を含む場合、sbt は NullPointerException による java.lang.ExceptionInInitializerError を投げて起動に失敗する。これをコンパイラに直させる方法の 1つとして、変数に lazy を付けて遅延変数として定義するという方法がある:

lazy val toolkit = "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit" % toolkitV

lazy val toolkitTest = "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit-test" % toolkitV

lazy val toolkitV = "0.2.0"

何でも lazy val を付けるのに渋い顔をする人もいるかもしれないが、僕たちは Scala 3 の lazy val は効率が良く、ビルド定義をコピー・ペーストに対して堅牢にすると思っている。

ライブラリ依存性の基本

このページは、sbt を使ったライブラリ依存性管理の基本を説明する。

sbt はマネージ依存性 (managed dependency) を実装するのに内部で Coursier を採用していて、Coursier、npm、PIP などのパッケージ管理を使った事がある人は違和感無く入り込めるだろう。

JAR ファイルを 1つ 1つ手でダウンロードする (アンマネージ依存性) 代わりに、マネージ依存性システムはサブプロジェクトで使われる外部ライブラリの取得を自動化する。Coursier のようなツールは宣言された ModuleID 列を解釈して、依存性解決 (全ての間接的依存性を展開して、バージョン衝突を解決して、正確なバージョンを決定する) を行い、結果となったアーティファクトをダウンロードしキャッシュして、一貫性のある JAR 管理を保証する。

libraryDependencies キー

依存性の宣言は、以下のようになる。ここで、groupId、artifactId、と revision は文字列だ:

libraryDependencies += groupID % artifactID % revision

もしくは、以下のようになる。このときの configuration は文字列もしくは Configuration の値だ (Test など)。

libraryDependencies += groupID % artifactID % revision % configuration

コンパイルを実行すると:

> compile

sbt は自動的に依存性を解決して、JAR ファイルをダウンロードする。

%% を使って正しい Scala バージョンを入手する

groupID % artifactID % revision のかわりに、 groupID %% artifactID % revision を使うと(違いは groupID の後ろの二つ連なった %%)、 sbt はプロジェクトの Scala のバイナリバージョンをアーティファクト名に追加する。これはただの略記法なので %% 無しで書くこともできる:

libraryDependencies += "org.scala-lang" % "toolkit_3" % "0.2.0"

ビルドの Scala バージョンが 3.x だとすると、以下の設定は上記と等価だ("org.scala-lang" の後ろの二つ連なった %% に注意):

libraryDependencies += "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit" % "0.2.0"

多くの依存ライブラリは複数の Scala バイナリバージョンに対してコンパイルされており、この機構はそのうちの中からプロジェクトとバイナリ互換性のある正しいものを選択する便利機能だ。

ライブラリ依存性を一箇所にまとめる

project 内の任意の .scala ファイルがビルド定義の一部となることを利用する一つの例として project/Dependencies.scala というファイルを作ってライブラリ依存性を一箇所にまとめるということができる。

// project/Dependencies.scala にこのファイルを置く

import sbt.*

object Dependencies:

// versions

lazy val toolkitV = "0.2.0"

// libraries

val toolkit = "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit" % toolkitV

val toolkitTest = "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit-test" % toolkitV

end Dependencies

この Dependencies オブジェクトは build.sbt 内で利用可能となる。 定義されている val が使いやすいように Dependencies.* を import しておこう。

import Dependencies.*

scalaVersion := "3.7.3"

name := "something"

libraryDependencies += toolkit

libraryDependencies += toolkitTest % Test

ライブラリ依存性の可視化

sbt シェルに Compile/dependencyTree と入力すると、ライブラリ依存性の間接的依存性を含むツリーが表示される:

> Compile/dependencyTree

これは以下のように表示されるはずだ:

sbt:bar> Compile/dependencyTree

[info] default:bar_3:0.1.0-SNAPSHOT

[info] +-org.scala-lang:scala3-library_3:3.3.1 [S]

[info] +-org.scala-lang:toolkit_3:0.2.0

[info] +-com.lihaoyi:os-lib_3:0.9.1

[info] | +-com.lihaoyi:geny_3:1.0.0

[info] | | +-org.scala-lang:scala3-library_3:3.1.3 (evicted by: 3.3.1)

[info] | | +-org.scala-lang:scala3-library_3:3.3.1 [S]

....

マルチプロジェクトの基本

簡単なプログラムならば単一プロジェクトから作り始めてもいいが、ビルドが複数の小さいのサブプロジェクトに分かれていくのが普通だ。

ビルド内のサブプロジェクトは、それぞれ独自のソースディレクトリを持ち、packageBin を実行すると独自の JAR ファイルを生成するなど、概ね通常のプロジェクトと同様に動作する。

サブプロジェクトは、lazy val を用いて Project 型の値を宣言することで定義される。例えば:

scalaVersion := "3.7.3"

LocalRootProject / publish / skip := true

lazy val core = (project in file("core"))

.settings(

name := "core",

)

lazy val util = (project in file("util"))

.dependsOn(core)

.settings(

name := "util",

)

val 定義された変数名はプロジェクトの ID 及びベースディレクトリの名前になる。ID は sbt シェルからプロジェクトを指定する時に用いられる。

sbt は必ずルートプロジェクトを定義するので、上の例のビルド定義は合計 3つのサブプロジェクトを持つ。

サブプロジェクト間依存性

あるサブプロジェクトを、他のサブプロジェクトにあるコードに依存させたい場合、dependsOn(...) を使ってこれを宣言する。例えば、util に core のクラスパスが必要な場合は util の定義を次のように書く:

lazy val util = (project in file("util"))

.dependsOn(core)

タスク集約

タスク集約は、集約する側のサブプロジェクトで任意のタスクを実行するとき、集約される側の複数のサブプロジェクトでも同じタスクが実行されるという関係を意味する。

scalaVersion := "3.7.3"

lazy val root = (project in file("."))

.autoAggregate

.settings(

publish / skip := true

)

lazy val util = (project in file("util"))

lazy val core = (project in file("core"))

上の例では、ルートプロジェクトが util と core を集約する。そのため、sbt シェルに compile と打ち込むと、3つのサブプロジェクトが並列にコンパイルされる。

ルートプロジェクト

ビルドのルートにあるサブプロジェクトは、ルートプロジェクトと呼ばれ、ビルドの中で特別な役割を果たすことがある。もしルートディレクトリにサブプロジェクトが定義されてない場合、sbt は自動的に他のプロジェクトを集約するデフォルトのルートプロジェクトを生成する。

コモン・セッティング

sbt 2.x では、settings(...) を使わずに build.sbt にセッティングを直書きした場合、コモン・セッティングとして全サブプロジェクトに注入される。

scalaVersion := "3.7.3"

lazy val core = (project in file("core"))

lazy val app = (project in file("app"))

.dependsOn(core)

上の例では、scalaVersion セッティングはデフォルトのルートプロジェクト、core、util に適用される。

既にサブプロジェクトにスコープ付けされたセッティングはこのルールの例外となる。

scalaVersion := "3.7.3"

lazy val core = (project in file("core"))

lazy val app = (project in file("app"))

.dependsOn(core)

// これは app のみに適用される

app / name := "app1"

この例外を利用して、以下のように、ルートプロジェクトにのみ適用されるセッティングを書くことができる:

scalaVersion := "3.7.3"

lazy val core = (project in file("core"))

lazy val app = (project in file("app"))

.dependsOn(core)

// これらは root にのみ適用される

LocalRootProject / name := "root"

LocalRootProject / publish / skip := true

プラグインの基本

プラグインとは何か

プラグインは、新しいセッティングやタスクを追加することでビルド定義を拡張する。例えば、プラグインを使って githubWorkflowGenerate というタスクを追加して、GitHub Actions のための YAML を自動生成することができる。

Scaladex を使ったプラグイン・バージョンの検索

Scaladex を用いてプラグインを検索して、そのプラグインの最新バージョンを探すことができる。

プラグインの宣言

ビルドが hello というディレクトリにあるとして、sbt-github-actions をビルド定義に追加したい場合、hello/project/plugins.sbt というファイルを作成して、プラグインの ModuleID を addSbtPlugin(...) に渡すことで、プラグイン依存性を宣言する:

// In project/plugins.sbt

addSbtPlugin("com.github.sbt" % "sbt-github-actions" % "0.28.0")

ビルドに sbt-assembly を追加する場合、以下を追加する:

// In project/plugins.sbt

addSbtPlugin("com.eed3si9n" % "sbt-assembly" % "2.3.1")

ソース依存性プラグインレシピには git リポジトリにホスティングされたプラグインを直接使う実験的技法が書かれてる。

プラグインは、通常サブプロジェクトに追加されるセッティングやタスクを提供することでその機能を実現する。次のセクションでその仕組みをもう少し詳しくみていく。

auto plugin の有効化と無効化

プラグインは、自身が持つセッティング群がビルド定義に自動的に追加されるよう宣言することができ、 その場合、プラグインの利用者は何もしなくてもいい。

auto plugin 機能は、セッティング群とその依存関係がサブプロジェクトに自動的、かつ安全に設定されることを保証する。auto plugin の多くはデフォルトのセッティング群を自動的に追加するが、中には明示的な有効化を必要とするものもある。

明示的な有効化が必要な auto plugin を使っている場合は、以下を build.sbt に追加する必要がある:

lazy val util = (project in file("util"))

.enablePlugins(FooPlugin, BarPlugin)

.settings(

name := "hello-util"

)

enablePlugins メソッドを使って、そのサブプロジェクトで使用したい auto plugin を明示的に定義できる。

逆に disablePlugins メソッドを使ってプラグインを除外することもできる。例えば、util から IvyPlugin のセッティングを除外したいとすると、build.sbt を以下のように変更する:

lazy val util = (project in file("util"))

.enablePlugins(FooPlugin, BarPlugin)

.disablePlugins(plugins.IvyPlugin)

.settings(

name := "hello-util"

)

明示的な有効化が必要か否かは、それぞれの auto plugin がドキュメントで明記しておくべきだ。あるプロジェクトでどんな auto plugin が有効化されているか気になったら、 sbt シェルから plugins コマンドを実行してみよう。

sbt:hello> plugins

In build /tmp/hello/:

Enabled plugins in hello:

sbt.plugins.CorePlugin

sbt.plugins.DependencyTreePlugin

sbt.plugins.Giter8TemplatePlugin

sbt.plugins.IvyPlugin

sbt.plugins.JUnitXmlReportPlugin

sbt.plugins.JvmPlugin

sbt.plugins.SemanticdbPlugin

Plugins that are loaded to the build but not enabled in any subprojects:

sbt.ScriptedPlugin

sbt.plugins.SbtPlugin

ここでは、plugins の表示によって sbt のデフォルトのプラグインが全て有効化されていることが分かる。 sbt のデフォルトセッティングは 7つのプラグインによって提供される:

CorePlugin: タスクの並列実行などのコア機能。DependencyTreePlugin: 依存性のツリー表示タスク。Giter8TemplatePlugin:sbt new機能の提供。IvyPlugin: モジュールの依存性解決と公開機能。JUnitXmlReportPlugin: junit-xml の生成。JvmPlugin: Java/Scala サブプロジェクトのコンパイル、テスト、実行、パッケージ化の機構。SemanticdbPlugin: SemanticDB の生成。

利用可能なプラグイン

ビルドのレイアウト

sbt は、知らない sbt ビルドを見てもだいたい勝手が分かるようにファイルをどこに置くかの慣習を持っている:

.

├── build.sbt

├── project/

│ ├── build.properties

│ ├── Dependencies.scala

│ └── plugins.sbt

├── src/

│ ├── main/

│ │ ├── java/

│ │ ├── resources/

│ │ ├── scala/

│ │ └── scala-2.13/

│ └── test/

│ ├── java/

│ ├── resources/

│ ├── scala/

│ └── scala-2.13/

├── subproject-core/

│ └── src/

│ ├── main/

│ └── test/

├─── subproject-util/

│ └── src/

│ ├── main/

│ └── test/

└── target/

.で表記したローカルのルートディレクトリはビルドのスタート地点だ。- ベース・ディレクトリは sbt 用語で、サブプロジェクトを構成するディレクトリを指す。上の例では、

.、subproject-core、subproject-utilは全てベース・ディレクトリだ。 - ビルド定義は、ローカルのルートディレクトリに置かれた

build.sbtにて記述される(実は*.sbtという名前のファイルなら何でもいい)。 - sbt のバージョンは

project/build.propertiesによって管理される。 - 生成されたファイル (コンパイルされたクラス、パッケージ化された JAR、マネージファイル、キャッシュ、ドキュメンテーションなど) はデフォルトでは

targetディレクトリに書き込まれる。

ビルドサポートファイル

In addition to build.sbt, project directory can contain .scala files that define helper objects and one-off plugins.

.

├── build.sbt

├── project/

│ ├── build.properties

│ ├── Dependencies.scala

│ └── plugins.sbt

....

project/ 内に .sbt ファイルを見かけることもあるかもしれないが、これらは通常プラグインを宣言するのに用いられる。プラグインの基本参照。

ソースコード

ソースコードに関して sbt は、デフォルトで Maven と同じディレクトリ構造を使う:

....

├── src/

│ ├── main/

│ │ ├── java/ <main Java sources>

│ │ ├── resources/ <files to include in main JAR>

│ │ ├── scala/ <main Scala sources>

│ │ └── scala-2.13/ <main Scala 2.13 specific sources>

│ └── test/

│ ├── java/ <test Java sources>

│ ├── resources/ <files to include in test JAR>

│ ├── scala/ <test Scala sources>

│ └── scala-2.13/ <test Scala 2.13 specific sources>

....

src/ 内の他のディレクトリは無視される。また、隠しディレクトリも無視される。

ソースコードは hello/app.scala のようにプロジェクトのベースディレクトリに置くこともできるが、小さいプロジェクトはともかくとして、通常のプロジェクトでは src/main/ 以下のディレクトリにソースを入れて整理するのが普通だ。

バージョン管理の設定

.gitignore (もしくは、他のバージョン管理システムの同様のファイル)には以下を追加しておくとよいだろう:

target/

ここでは(ディレクトリだけにマッチさせるために)語尾の / を意図的につけていて、一方で (普通の target/ に加えて project/target/ にもマッチさせるために)先頭の / は意図的に つけていないことに注意。

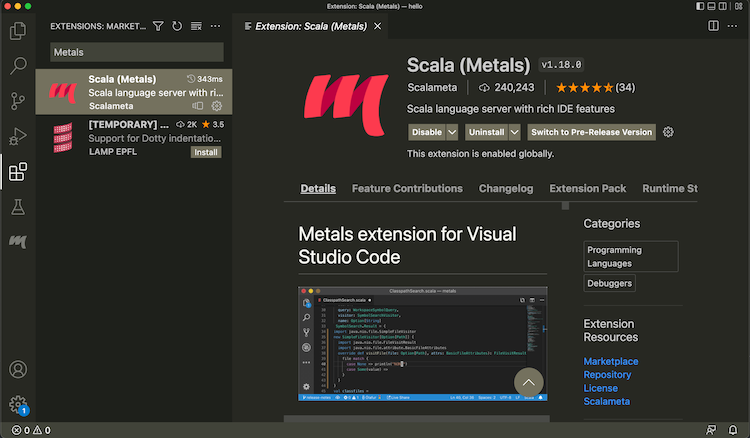

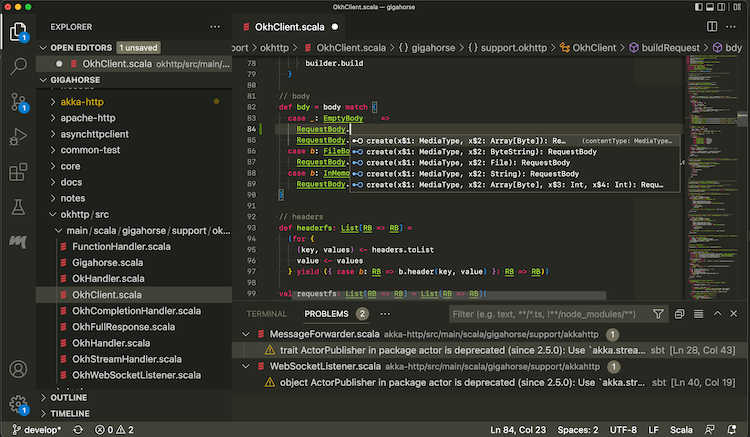

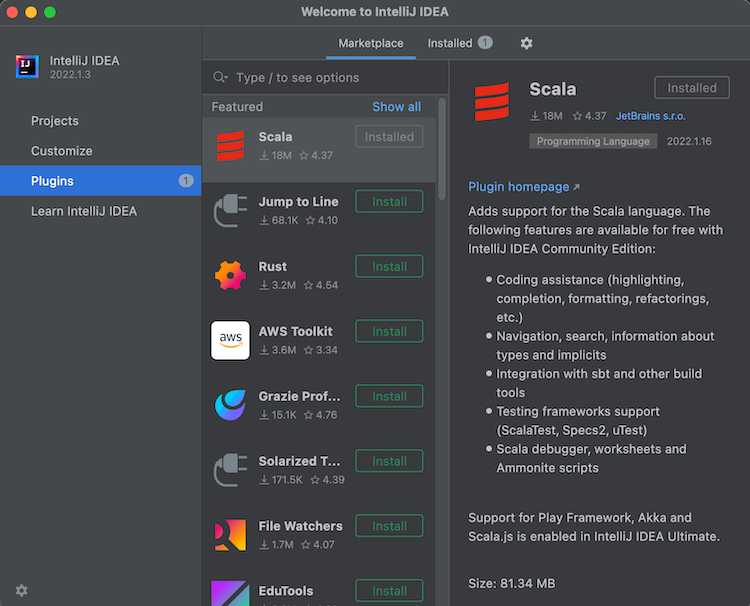

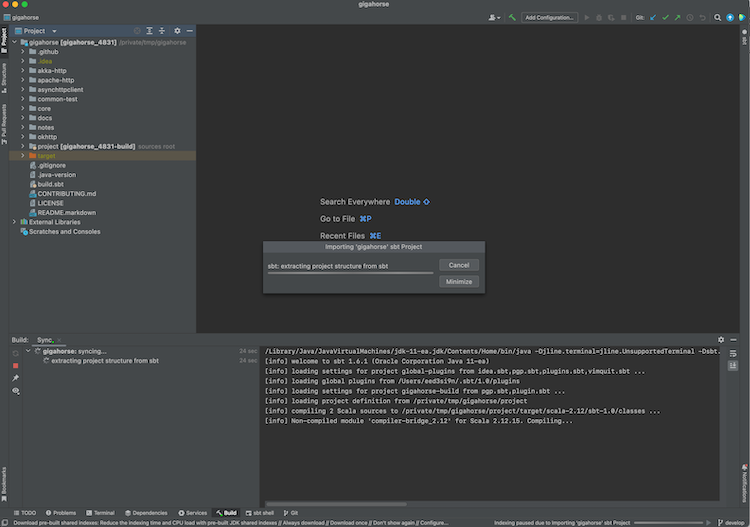

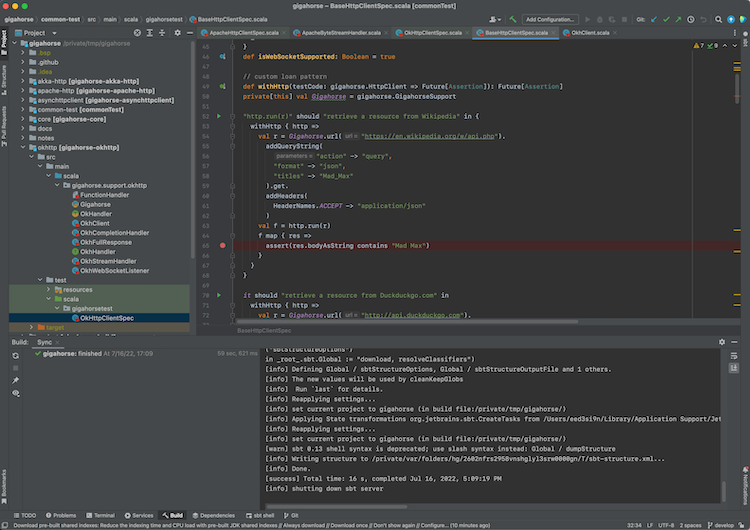

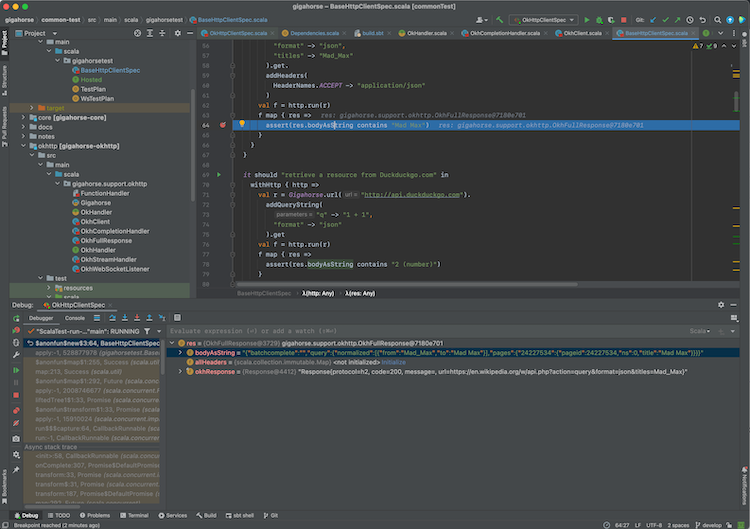

sbt と IDE

エディタと sbt だけで Scala のコードを書くことも可能だが、今日日のプログラマの多くは統合開発環境 (IDE) を用いる。Scala の IDE は Metals と IntelliJ IDEA の二強で、それぞれ sbt ビルドとの統合をサポートする。

IDE を使う利点をいくつか挙げると:

- 定義へのジャンプ

- 静的型付けに基づくコード補完

- コンパイルエラーの列挙と、エラー地点へのジャンプ

- インタラクティブなデバッグ

IDE 統合のためのレシピをここにいくつか紹介する:

変更点

sbt 2.0 の変更点

互換性に影響のある変更点

- Scala 3 を用いたメタビルド。ビルド定義やプラグインに使われる sbt 2.x build.sbt DSL は Scala 3.x ベースとなった (現行では 3.7.3) (sbt 1.x 並びに 2.x は、Scala 2.x と 3.x の両方をビルドすることが可能) by @eed3si9n, @adpi2, and others.

- コモン・セッティング。build.sbt に直書きされたセッティングは、ルートサブプロジェクトだけではなく、全てのサブプロジェクトに追加され、これまで

ThisBuildが受け持ってきた役目を果たすことができる。 - 差分テスト。

testは、テスト結果をキャッシュする差分テストへと変更された。全テストを走らせたい場合はtestFullを使う by @eed3si9n in #7686 - キャッシュ化されたタスク。全てのタスクはデフォルトで、キャッシュ化されている。詳細はキャッシュ参照。

- 依存性のツリー表示。

dependencyTree関連のタスク群は 1つのインプット・タスクに統一された by @eed3si9n in #8199 testタスクの形がUnitからTestResultへと変更された by @eed3si9n in #8181- 以前

URLに型付けされていたデフォルトのセッティングやタスクキー (apiMappings,apiURL,homepage,organizationHomepage,releaseNotesURLなど) はURIに変更された in #7927 licenseキーの型がSeq[(String, URL)]からSeq[License]へと変更された in #7927- sbt 2.x プラグインは

_sbt2_3という suffix を用いて公開される by @eed3si9n in #7671 - sbt 2.x は、

platformセッティングを追加して、ModuleIDの%%%演算子を使わなくても、%%演算子だけで JVM、JS、Native のクロスビルドができるようにした by @eed3si9n in #6746 useCoursierセッティングを廃止して、Coursier をオプトアウトできないようにした by @eed3si9n in #7712Key.Classpath型は、Seq[Attributed[File]]からSeq[Attributed[xsbti.HashedVirtualFileRef]]型のへのエイリアスへと変更された。同様に、以前Fileを返していたタスクキーのいくつかはHashedVirtualFileRefを返すように変更された。ファイルのキャッシュ化も参照。- sbt 2.x では、

targetのデフォルトが<subproject>/target/からtarget/out/jvm/scala-3.7.3/<subproject>/へと変更された。 - sbt 2.x は

build.sbtに変更があると、デフォルトで自動的リロードされるようになった @eed3si9n in #8211 - 自動的タスク集約を行う

Project#autoAggregateが追加された @eed3si9n in #8290

勧告どおり廃止された機能

新機能

- project matrix。sbt 1.x からプラグインで使用可能だった project matrix が本体に取り込まれ、並列クロスビルドができるようになった。

- sbt クエリ。sbt 2.x は統一スラッシュ構文を拡張してサブプロジェクトのクエリを可能とする。詳細は下記参照。

- ローカル/リモート兼用のキャッシュ・システム。詳細は下記参照。

- クライアントサイド・ラン。詳細は下記参照。

コモン・セッティング

sbt 2.x では、build.sbt に直書きされたセッティングはコモン・セッティングとして解釈され、全サブプロジェクトに注入される。そのため、ThisBuild スコープ付けを使わずに scalaVersion を設定できる:

scalaVersion := "3.7.3"

さらに、これはいわゆる動的ディスパッチ問題を解決する:

lazy val hi = taskKey[String]("")

hi := name.value + "!"

sbt 1.x では hi タスクはルートプロジェクトの名前を捕捉してしまっていたが、sbt 2.x は各サブプロジェクトの name に ! を追加する:

$ sbt show hi

[info] entering *experimental* thin client - BEEP WHIRR

[info] terminate the server with `shutdown`

> show hi

[info] foo / hi

[info] foo!

[info] hi

[info] root!

これは、@eed3si9n によって #6746 としてコントリされた。

sbt クエリ

サブプロジェクトが複数あるとき、選択範囲を狭めるのに sbt 2.x は sbt クエリを導入する。

$ sbt foo.../test

上の例では、foo から始まる全てのサブプロジェクトを実行する。

$ sbt ...@scalaBinaryVersion=3/test

上の例では、scalaBinaryVersion が 3 の全てのサブプロジェクトを実行する。これは、@eed3si9n によって #7699 としてコントリされた。

差分テスト

sbt 2.x では、test タスクはインプット・タスクとなって、実行するテスト・スイートをフィルターできるようになった:

> test *Example*

さらに、test はキャッシュ化された差分テストとなった。そのため、以前にテストが失敗したか、前回の実行から何かが変更されないと実行されないようになった。

詳細は test 参照

ローカル/リモート兼用のキャッシュ・システム

sbt 2.x は、デフォルトでキャッシュ化されたタスクを実装するため、自動的にタスクの結果をローカルのディスクもしくは Bazel 互換のリモートキャッシュにてキャッシュ化することができる。

lazy val task1 = taskKey[String]("doc for task1")

task1 := name.value + version.value + "!"

これは task1 への入力を追跡してマシン・ワイドなディスクキャッシュを作成する。これはリモート・キャッシュとしても設定できるようになっている。sbt タスクはファイルを生成することがよくあるので、ファイルのコンテンツをキャッシュ化できる仕組みも提供する。

lazy val task1 = taskKey[String]("doc for task1")

task1 := {

val converter = fileConverter.value

....

val output = converter.toVirtualFile(somefile)

Def.declareOutput(output)

name.value + version.value + "!"

}

詳細はキャッシュ化を参照。これは @eed3si9n によって #7464 / #7525 としてコントリされた。

クライアントサイド・ラン

sbt runner 1.10.10 以降は sbt 2.x を起動するのに、デフォルトで sbtn (GraalVM native-image のクライアント) を使う。sbt 2.0 は run タスクを sbtn に送り返して、sbtn 側で新しい JVM にフォークさせる。以下のように実行するだけでいい:

sbt run

これは、sbt server をブロックしてしまうことを回避し、かつ複数の実行を行うことができる。これは @eed3si9n によって#8060 としてコントリされた。run ドキュメンテーション参照。

性能の改善

Adrien Piquerez さんが Scala Center に在籍していたときに、性能改善に関連するコントリをいくつか行った。

- perf: 長生きするオブジェクトの数を削減して、2.0.0-M2 比較で起動を 20% 高速化した by @adpi2 in #7866

- perf:

SettingとInitializeが作成される数を削減した by @adpi2 in #7880 - perf:

Settingsをリファクタリングして、集約キーのインデックス化を最適化した @adpi2 in #7879 - perf:

InfoとBasicAttributeMapのインスタンスを削除した by @adpi2 in #7882

過去の変更点

以下も参照:

sbt 1.x からのマイグレーション

build.sbt DSL の Scala 3.x への移行

念の為書いておくと、sbt 1.x 系 2.x 系のどちらを使ってもScala 2.x および Scala 3.x 両方のプログラムをビルドすることが可能だ。ただし、build.sbt DSL を裏付ける Scala は sbt のバージョンによって決定される。sbt 2.0 では、Scala 3.7.x 系に移行する。

そのため、sbt 2.x 用のカスタムタスクや sbt プラグインを実装する場合、それは Scala 3.x を用いて行われることとなる。Scala 3.x に関する詳細はScala 3.x incompatibility table や Scala 2 with -Xsource:3 なども参照。

// This works on Scala 2.12.20 under -Xsource:3

import sbt.{ given, * }

Import given

Scala 2.x と 3.x の違いの 1つとして、型クラスのインスタンスの言語スコープへの取り込み方の違いが挙げられる。Scala 2.x では import FooCodec._ と書いたが、Scala 3 は、import FooCodec.given と書く。

// 以下は、sbt 1.x と 2.x の両方で動作する

import sbt.librarymanagement.LibraryManagementCodec.{ given, * }

後置記法の回避

特に ModuleID 関連で、 sbt 0.13 や 1.x のコード例で後置記法を見ることは珍しく無かった:

// BAD

libraryDependencies +=

"com.github.sbt" % "junit-interface" % "0.13.2" withSources() withJavadoc()

これは、sbt 2.x では起動に失敗する:

-- Error: /private/tmp/foo/build.sbt:9:61 --------------------------------------

9 | "com.github.sbt" % "junit-interface" % "0.13.2" withSources() withJavadoc()

| ^^

|can't supply unit value with infix notation because nullary method withSources

in class ModuleIDExtra: (): sbt.librarymanagement.ModuleID takes no arguments;

use dotted invocation instead: (...).withSources()

これを修正するには、普通の (ピリオドを使った) 関数呼び出しの記法で書く:

// GOOD

libraryDependencies +=

("com.github.sbt" % "junit-interface" % "0.13.2").withSources().withJavadoc()

ベア・セッティングの変更点

version := "0.1.0"

scalaVersion := "3.7.3"

settings(...) を介さず、上の例のように build.sbt に直書きされたセッティングをベア・セッティング (bare settings) と呼ぶ。

sbt 1.x において、ベア・セッティングはルートプロジェクトにのみ適用されるセッティングだった。sbt 2.x においては、build.sbt のベア・セッティングは全サブプロジェクトに注入されるコモン・セッティングとして解釈される。

name := "root" // 全サブプロジェクトの名前が root になる!

publish / skip := true // 全サブプロジェクトがスキップされる!

ルートプロジェクトにのみセッティングを適用させるためには、マルチ・プロジェクトなビルドを定義するか、セッティングを LocalRootProject にスコープ付けさせる:

LocalRootProject / name := "root"

LocalRootProject / publish / skip := true

ThisBuild のマイグレーション

sbt 2.x においては、ベア・セッティングが ThisBuild にスコープ付けされる場面は無くなったはずだ。コモン・セッティングの ThisBuild に対する利点として委譲の振る舞いが、分かりやすくなるということがある。これらのセッティングはプラグインのセッティングと、settings(...) の間に入るため、 Compile / scalacOptions といったセッティングを定義するのに使える。 ThisBuild ではそれは不可能だった。

Changes to exportJars

exportJars defaults to true, was false. This might break getResource("/") and resource.toURI. Set exportJars := false if this logic is broken in your build, producing NullPointerExceptions and FileSystemNotFoundExceptions. Set exportJars := false in your build if you want to keep the old behavior. The change was introduced by sbt/sbt#7464, see also blog.

キャッシュ・タスクへのマイグレーション

キャッシュ化のオプトアウトを含めキャッシュ・タスク参照。

IntegrationTest の廃止

IntegrationTest コンフィギュレーションの廃止に対応するためには、別のサブプロジェクトを定義して、普通のテストとして実装するのが推奨される。

スラッシュ構文へのマイグレーション

sbt 1.x は sbt 0.13 スタイル構文とスラッシュ構文の両方をサポートしたきた。2.x で sbt 0.13 構文のサポートが無くなるので、sbt シェルと build.sbt の両方で統一スラッシュ構文を使う:

<project-id> / Config / intask / key

具体的には、test:compile という表記はシェルからは使えなくなる。代わりに Test/compile と書く。build.sbt ファイルの半自動的なマイグレーションには統一スラッシュ構文のための syntactic Scalafix rule 参照。

scalafix --rules=https://gist.githubusercontent.com/eed3si9n/57e83f5330592d968ce49f0d5030d4d5/raw/7f576f16a90e432baa49911c9a66204c354947bb/Sbt0_13BuildSyntax.scala *.sbt project/*.scala

sbt プラグインのクロスビルド

sbt 2.x では、sbt プラグインを Scala 3.x と 2.12.x に対してクロスビルドすると自動的に sbt 1.x 向けと sbt 2.x 向けにクロスビルドするようになっている。

// sbt 2.x を使った場合

lazy val plugin = (projectMatrix in file("plugin"))

.enablePlugins(SbtPlugin)

.settings(

name := "sbt-vimquit",

)

.jvmPlatform(scalaVersions = Seq("3.6.2", "2.12.20"))

projectMatrix を使った場合、プラグインを plugin/ のようなサブディレクトリに移動させる必要がある。そうしないと、デフォルトのルートプロジェクトも src/ を拾ってしまうからだ。

sbt 1.x を使った sbt プラグインのクロスビルド

sbt 1.x を使ってクロスビルドする場合 sbt 1.10.2 以降を使う必要がある。

// sbt 1.x を使った場合

lazy val scala212 = "2.12.20"

lazy val scala3 = "3.6.2"

ThisBuild / crossScalaVersions := Seq(scala212, scala3)

lazy val plugin = (project in file("plugin"))

.enablePlugins(SbtPlugin)

.settings(

name := "sbt-vimquit",

(pluginCrossBuild / sbtVersion) := {

scalaBinaryVersion.value match {

case "2.12" => "1.5.8"

case _ => "2.0.0-RC6"

}

},

)

%% の変更点

sbt 2.x において ModuleID の %% 演算子は多プラットフォームに対応するようになった。JVM系のサブプロジェクトは、%% は以前同様に Maven リポジトリにおける (_3 のような) Scala バージョンの接尾辞をエンコードする。

%%% 演算子のマイグレーション

Scala.JS や Scala Native の sbt 2.x の対応ができるようになった場合、%% は (_3 のような) Scala バージョンと (_sjs1 その他の) プラットフォーム接尾辞をエンコードできるようになっている。そのため、%%% は %% に置き換えれるようになるはずだ:

libraryDependencies += "org.scala-js" %% "scalajs-dom" % "2.8.0"

JVM ライブラリが必要な場合は .platform(Platform.jvm) を使う。

target に関する変更

sbt 2.x では、target ディレクトリが単一の target/ ディレクトリに統一され、それぞれのサブプロジェクトがプラットフォーム、Scala バージョン、id をエンコードしたサブディレクトリを作る。scripted test でこの変更点を吸収するために、exists、absent、delete のコマンドは glob式 ** および || をサポートする。

# before

$ absent target/out/jvm/scala-3.3.1/clean-managed/src_managed/foo.txt

$ exists target/out/jvm/scala-3.3.1/clean-managed/src_managed/bar.txt

# after

$ absent target/**/src_managed/foo.txt

$ exists target/**/src_managed/bar.txt

# どちらでも ok

$ exists target/**/proj/src_managed/bar.txt || proj/target/**/src_managed/bar.txt

PluginCompat 技法

同じ *.scala ソースから sbt 1.x と 2.x 向けのプラグインを作るには「詰め木」的なコードとして PluginCompat という名前のオブジェクトをsrc/main/scala-2.12/ と src/main/scala-3/ の両方に入れて違いを吸収することができる。

Classpath 型のマイグレーション

sbt 2.x からは Classpath 型がSeq[Attributed[xsbti.HashedVirtualFileRef]] 型のエイリアスとなった。以下は、sbt 1.x と 2.x の両方のクラスパスに対応するための詰め木だ。

// src/main/scala-3/PluginCompat.scala

package sbtfoo

import java.nio.file.{ Path => NioPath }

import sbt.*

import xsbti.{ FileConverter, HashedVirtualFileRef, VirtualFile }

private[sbtfoo] object PluginCompat:

type FileRef = HashedVirtualFileRef

type Out = VirtualFile

def toNioPath(a: Attributed[HashedVirtualFileRef])(using conv: FileConverter): NioPath =

conv.toPath(a.data)

inline def toFile(a: Attributed[HashedVirtualFileRef])(using conv: FileConverter): File =

toNioPath(a).toFile()

def toNioPaths(cp: Seq[Attributed[HashedVirtualFileRef]])(using conv: FileConverter): Vector[NioPath] =

cp.map(toNioPath).toVector

inline def toFiles(cp: Seq[Attributed[HashedVirtualFileRef]])(using conv: FileConverter): Vector[File] =

toNioPaths(cp).map(_.toFile())

end PluginCompat

これが sbt 1.x 用だ:

// src/main/scala-2.12/PluginCompat.scala

package sbtfoo

import sbt.*

private[sbtfoo] object PluginCompat {

type FileRef = java.io.File

type Out = java.io.File

def toNioPath(a: Attributed[File])(implicit conv: FileConverter): NioPath =

a.data.toPath()

def toFile(a: Attributed[File])(implicit conv: FileConverter): File =

a.data

def toNioPaths(cp: Seq[Attributed[File]])(implicit conv: FileConverter): Vector[NioPath] =

cp.map(_.data.toPath()).toVector

def toFiles(cp: Seq[Attributed[File]])(implicit conv: FileConverter): Vector[File] =

cp.map(_.data).toVector

// This adds `Def.uncached(...)`

implicit class DefOp(singleton: Def.type) {

def uncached[A1](a: A1): A1 = a

}

}

これで PluginCompat.* を import して toNioPaths(...) などを使って sbt 1.x と 2.x の違いを吸収できる。特にこれは、クラスパス型の違いを吸収して NIO Path ベクトルに変換できることを示している。

コンセプト

コマンド

コマンドは、システム・レベルでの sbt の構成要素で、ユーザや IDE とのやり取りを捕捉する。

便宜的に、各コマンドは State => State への関数だと考えることができる。 sbt において状態 (state) は以下を表す。

- ビルド構造 (

build.sbtなど) - ディスク (ソースコード、JAR 成果物など)

そのため、コマンドは通常ビルド構造もしくはディスクを変更する。例えば、set コマンドはセッティングを適用してビルド構造を変更する。

> set name := "foo"

act コマンドは、compile のようなタスクをコマンドに持ち上げる:

> compile

コンパイルはディスクからの読み込みを行い、アウトプットをディスクに書き込むか画面にエラーメッセージを表示する。

コマンドは逐次処理される

状態は 1つしか存在しないものなので、コマンドは 1つづつ実行されるという特徴がある。

一部例外もあるが、基本的にコマンドは逐次実行される。メンタルモデルとしては、コマンドはカフェで注文を受け取るレジ係で、注文の順番に処理が行われると考えることができる。

タスクは並列実行される

前述の通り、act コマンドはタスクをコマンドのレベルに持ち上げる。その際に act コマンドは、集約されたサブプロジェクトにタスクを転送して、独立したタスクを並列実装する。

同様に、セッション起動時に実行される reload コマンドはセッティングを並列に初期化する。

sbt server の役割

sbt server は、コマンドラインもしくは Build Server Protocol と呼ばれるネットワーク API 経由からコマンドを受け取ることができるサービスだ。この機構によって、ビルドユーザと IDE が同一の sbt セッションを共有することができる。

クロスビルド

同じソースファイルの集合から複数のターゲットに対してビルドすることをクロスビルドと呼ぶ。これは、複数の Scala リリースを対象とする Scala クロスビルド、JVM、Scala.JS、Scala Native を対象とするプラットフォーム・クロスビルド、Spark バージョンのような仮想軸を含む。

クロスビルドされたライブラリの使用

複数の Scala バージョンに対してビルドされたライブラリを使うには ModuleID の最初の % を 2重に %% とする。これは、依存性の名前に Scala ABI (アプリケーション・バイナリ・インターフェイス) サフィックスを付随するという sbt への指示となる。具体例を用いて説明すると:

libraryDependencies += "org.typelevel" %% "cats-effect" % "3.5.4"

現行 Scala バージョンが Scala 3.x であるならば、上の例は以下と等価となる:

libraryDependencies += "org.typelevel" % "cats-effect_3" % "3.5.4"

セットアップに関しては、cross building setup 参照。

歴史的経緯

Scala の初期時代 (Scala 2.9 以前) は、Scala 標準ライブラリがパッチレベルでもバイナリ互換性を保たなかったため、新しい Scala バージョンがリリースされるたびに全ライブラリが、新しい Scala バージョンに対して再リリースされる必要があった。そのため、ライブラリのユーザ側は、自分が使う Scala バージョンに互換の特定のライブラリのバージョンを選ぶ必要があった。

Scala 2.9.x 以降も Scala 標準ライブラリはマイナーレベルでの互換性を持たなかったため、Scala 2.10.x に対してコンパイルされたライブラリは 2.11.x と互換性を持たなかった。

これらの問題の対策として、sbt は以下の特徴を持つクロスビルド機構を開発した:

- 同じソース・ファイルの集合から、複数の Scala バージョンに対してコンパイルできる

- Maven のアーティファクト名に ABI バージョン (

_2.12など) を付随するという慣例を定義した - この機構は Scala.JS その他のプラットフォームもサポートするよう拡張された

Project matrix

sbt 2.x introduces project matrix, which enables cross building to happen in parallel.

organization := "com.example"

scalaVersion := "3.7.3"

version := "0.1.0-SNAPSHOT"

lazy val core = (projectMatrix in file("core"))

.settings(

name := "core"

)

.jvmPlatform(scalaVersions = Seq("3.7.3", "2.13.17"))

セットアップに関しては、cross building setup 参照。

sbt クエリ

sbt 2.x はスラッシュ構文を拡張してサブプロジェクトの集約を可能とする:

act ::= [ query / ] [ config / ] [ in-task / ] ( taskKey | settingKey )

言い換えると、sbt クエリはサブプロジェクト軸の新しい書き方だと言える。

サブプロジェクトの参照

サブプロジェクトの参照は、サブプロジェクトを選択するクエリとしてそのまま使える:

上のようなビルドがあるとき、sbt 1.x と同様の構文を使って foo サブプロジェクトのテストを実行できる:

foo/test

... ワイルドカード

... ワイルドカードはどの文字列にもマッチして、他の文字や数字とも組み合わせて、ルートの集約リストを絞り込むことができる。例えば、以下のようにして foo で始まる全サブプロジェクトのテストを実行することができる:

foo.../test

sbt クエリは、直感的に分かりやすそうな * (アスタリスク) でなく、意図的に ... (ドット・ドット・ドット) を採用する。これは * がシェル環境においてワイルドカードとして使われることが多いからだ。そのため、常にクォートで囲む必要があり、また */test をクォートし忘れると src/test のようなディレクトリにマッチしてしまう可能性が高い。

@scalaBinaryVersion パラメータ

@scalaBinaryVersion パラメータは、サブプロジェクトの scalaBinaryVersion セッティングにマッチする。

val toolkitV = "0.5.0"

val toolkit = "org.scala-lang" %% "toolkit" % toolkitV

lazy val foo = projectMatrix

.settings(

libraryDependencies += toolkit,

)

.jvmPlatform(scalaVersions = Seq("3.7.3", "2.13.17"))

lazy val bar = projectMatrix

.settings(

libraryDependencies += toolkit,

)

.jvmPlatform(scalaVersions = Seq("3.7.3", "2.13.17"))

例えば、全ての 3.x サブプロジェクトのテストを以下のように実行できる:

...@scalaBinaryVersion=3/test

以下のように、ターミナル上からも使うことができる:

$ sbt ...@scalaBinaryVersion=3/test

[info] entering *experimental* thin client - BEEP WHIRR

[info] terminate the server with `shutdown`

> ...@scalaBinaryVersion=3/test

[info] Passed: Total 0, Failed 0, Errors 0, Passed 0

[info] No tests to run for Test / testQuick

[info] compiling 1 Scala source to /tmp/foo/target/out/jvm/scala-3.6.4/foo/test-backend ...

[info] Passed: Total 0, Failed 0, Errors 0, Passed 0

[info] No tests to run for bar / Test / testQuick

example.ExampleSuite:

+ Scala version 0.003s

[info] Passed: Total 1, Failed 0, Errors 0, Passed 1

projectMatrix を使っていると集約サブプロジェクトの絞り込みが欲しくなる場面が多々あるが、sbt クエリがこれが解決する。

キャッシュ化

sbt 2.0 は、ローカル/リモートの両方で使えるハイブリッドなキャッシュ・システムを導入し、タスク結果をローカルのディスクもしくは、Bazel 互換のリモート・キャッシュにキャッシュ化することができる。 過去のリリースを通じて、sbt は update のキャッシュ、差分コンパイルなど、様々なキャッシュ化を実装してきたが、sbt 2.x のキャッシュはいくつかの理由により、大きな変化となる:

- 自動化。sbt 1.x ではプラグイン作者がタスク実装内でキャッシュ化関数を呼び出す必要があったが、sbt 2.x キャッシュはタスク・マクロに組み込まれているため、自動化されている。

- マシン・ワイド。sbt 2.x のディスク・キャッシュはマシン上の全ビルドから共有されている。

- リモート対応。sbt 2.x では、キャッシュのストレージは独立して設定可能なため、全てのキャッシュ可能なタスクは自動的にリモート・キャッシュに対応している。

キャッシュ化の全体目標は、コード量が増えるにつれて増加していくビルドとテスト時間の成長率を現状よりも平たく抑えることにある。そのため、高速化の比率はコード量などにもよるが、現行のテストに 10分以上かかるようなビルドの場合、5倍から 20倍を狙っていくことも可能となってくる。

キャッシュ化の基本

ビルドプロセスがあたかも (A1, A2, A3, ...) というインプットを受け取り、 (R1, List(O1, O2, O3, ...)) というアウトプットを返す純粋関数であるかのように扱うというのがキャッシュ化の基本的な考えだ。例えば、ソース・ファイルのリストと Scala バージョンを受け取って、*.jar ファイルを生成することができる。もし仮定が成立するなら、同一のインプットに対してはアウトプットの JAR を全員に対してメモ化できる。メモ化された JAR を使うほうが、Scala コンパイルのような実際のタスクを実行するよりも高速であることがこのような技法を使うメリットとなる。

密閉ビルド

「純粋関数としてのビルド」のメンタルモデルとして、ビルド界隈のエンジニアは密閉ビルド (hermetic build)、つまり砂漠の真ん中に置かれたコンテナの中で時計も Internet も無い状態で行われるビルドという用語を使うことがある。そのような状態で JAR ファイルを生成することができれば、その JAR ファイルはどのマシンと共有しても大丈夫なはずだ。何故時計の話が出てきたのだろうか? それは、JAR ファイルが仕様としてタイムスタンプを捕捉するため、毎回少しづつ違った JAR を生成するからだ。これを回避するために、「密閉な」ビルドツールはいつビルドが実行されてもタイムスタンプを 2010-01-01 に上書きする慣習がある。

逆に、不安定なインプットを捕捉してしまったビルドは「密閉性を壊した」、または「非密閉である」という。密閉性が壊れるもう 1つのよくあるパターンは、インプットもしくはアウトプットで絶対パスを捕捉してしまうことだ。時としてはパスはマクロ経由で JAR に入ってしまう事があるので、バイトコードの差を検査しないと発見できないかもしれない。

自動的キャッシュ化

以下に、自動的キャッシュ化を具体例を用いて解説する:

val someKey = taskKey[String]("something")

someKey := name.value + version.value + "!"

sbt 2.x では、このタスクの結果は、name と version という 2つのセッティングの値に基づいて自動的にキャッシュ化される。最初にこのタスクが実行されたときには、オンサイトで実行され、2回目以降はディスク・キャッシュの値が用いられる:

sbt:demo> show someKey

[info] demo0.1.0-SNAPSHOT!

[success] elapsed time: 0 s, cache 0%, 1 onsite task

sbt:demo> show someKey

[info] demo0.1.0-SNAPSHOT!

[success] elapsed time: 0 s, cache 100%, 1 disk cache hit

キャッシュ化はシリアライゼーション問題と同等に困難だ

キャッシュの自動化に参加するためには、(name や version などの) インプットキーは sjsonnew.HashWriter 型クラスの given、戻り値は sjsonnew.JsonFormat 型クラスの given を提供する必要がある。Contraband を使って sjson-new のコーデックを生成することができる。

ファイルのキャッシュ化

ファイル (java.io.File など) のキャッシュ化は特別な配慮を必要とするが、それは技術的に難しいからというよりは、ファイルが関わったときに発生する曖昧さと思い込みによる所が大きい。一言に「ファイル」といっても、実は様々なことを意味する:

- 取り決められた場所からの相対パス

- 現物化された実際のファイル

- コンテンツ・ハッシュ値などの一意的なファイルの証明

厳密には、File はファイルパスのみを指すため、target/a/b.jar というようなファイル名のみを復元すればいい。これは、下流のタスクが target/a/b.jar というファイルがファイル・システムに存在すると思い込んでいた場合失敗してしまう。これを明瞭化しつつ、絶対パスを回避するために、sbt 2.x は 3つのそれぞれの場合に対して別々の型を提供する。

xsbti.VirtualFileRefは、ただの相対パスのみを表すのに用いられ、これは文字列を渡すのと等価だxsbti.VirtualFileは、コンテンツを持つ現物化されたファイルを表し、仮想ファイルもしくはディスク上のファイルであってもいい

しかしながら、密閉ビルドという観点から見ると、ファイルのリストを表すのにどちらも優れていない。ファイル名のみを持っていてもファイルが同一性を保証できないし、ファイルの全コンテンツを持ち回すのは JSON などに使うには非効率的だ。

ここで謎の 3つ目方法、ファイルの一意的な証明が便利になる。HashedVirtualFileRef は、相対パスの他にも SHA-256 コンテンツ・ハッシュとファイル・サイズを追跡する。これは、JSON に簡単にシリアライズできるが、特定のファイルを参照することもできる。

ファイル作成の作用

ファイルを生成するが、VirtualFile を戻り値の型として使わないタスクがたくさんある。例えば、sbt 1.x では compile は Analysis を返し、*.class ファイルの生成は「副作用」として行われる。

キャッシュ化に参加するためには、これらの作用も後に残しておきたいものとして宣言する必要がある。

someKey := {

val conv = fileConverter.value

val out: java.nio.file.Path = createFile(...)

val vf: xsbti.VirtualFile = conv.toVirtualFile(out)

Def.declareOutput(vf)

vf: xsbti.HashedVirtualFileRef

}

リモート・キャッシュ

オプションとして、ビルドを拡張してローカルでのディスク・キャッシュの他にリモート・キャッシュも使うことができる。リモート・キャッシュは、複数のマシンがビルドの成果物やアウトプットを共有することでビルドの性能を向上できる。

自分のプロジェクトもしくは会社に 10名ぐらいのメンバーがいると想像してほしい。毎朝、その 10名の書いた変更を git pull で取り込んで、書かれたコードをビルドする必要がある。プロジェクトが順調にいけば、コード量は時間とともに増加していき、一日のうち他人のコードをビルドする時間の割合も増えていく。これは、いずれチーム規模とコード量の制限要因となる。リモート・キャッシュは、CI システムにキャッシュを補給させ自分たちは成果物やタスクのアウトプットをダウンロードできるようにすることでこの傾向を逆転させる。

sbt 2.x は、Bazel 互換の gRPC インターフェイスを実装するため、オープンソース及び商用の複数のバックエンド・システムと統合する。詳細は、リモート・キャッシュのセットアップ参照。

レファレンス

キャッシュ・タスクのレファレンスガイドも参照。

レファレンス

sbt

基本的な導入としては、sbt 入門ガイドの基本タスクをまず読んでみてほしい。

書式

sbt

sbt command args

sbt --server

sbt --script-version

説明

sbt は最初は Scala と Java のために作られたシンプルなビルド・ツールだ。sbt はサブプロジェクト、様々な依存性、カスタムタスクなどを宣言することで高速かつ再現性の高いビルドが得られることを保証する。

sbt runner と sbt server

- sbt runner は

sbtという名前のシステム・シェル・スクリプトで、Windows ではsbt.batと呼ばれる。これは、どのバージョンの sbt でも実行することが可能で、これは「sbt という名前のシェル・スクリプト」とも呼ばれる。- sbt 2.x が検知されると、sbt runner は、典型的には GraalVM ネイティブで実装されたクライアント・プログラムである sbtn を用いて、クライアント・モードで実行する。

- sbt runner は sbt ランチャーという、全てのバージョンの sbt を起動できるランチャーを実行する。

- sbt をインストールした場合、インストールされるのは sbt runner だ。

- sbt server は、sbt の本体で、実際のビルドツールだ。

- sbt のバージョンは、それぞれのワーキング・ディレクトリ内にある

project/build.propertiesによって決定される。 - sbt server は、sbtn、ネットワーク API、もしくは独自の sbt シェルのいずれかからコマンドを受け取る。

- sbt のバージョンは、それぞれのワーキング・ディレクトリ内にある

sbt.version=2.0.0-RC6

この機構によってビルドを特定のバージョンの sbt に設置することができ、プロジェクトで作業する人全員が、マシンにインストールされた sbt runner に関わらず同一のビルド意味論を共有できるようになる。

このような分割があるため、機能の一部は sbt runner や sbtn のレベルで実装され、その他の機能は sbt server レベルで実装される。

sbt コマンド

sbt には、サブプロジェクトのレベルで動作するタスク (compile など) とビルド定義そのものを操作することも可能な狭義のコマンド (set など) がある。

しかし、act コマンドによってセッティングやタスクもコマンドに持ち上げることが可能なため「sbt シェルに打ち込むことができるもの全て」を広義のコマンドとしても解釈できる。

詳細はコマンドのコンセプトのページを参照。

サブプロジェクト・レベルのタスク

clean生成されたファイル (targetディレクトリ) を削除する。publishpublishToセッティングで指定されたリポジトリにJAR ファイルなどのアーティファクトを公開する。publishLocalJAR ファイルなどのアーティファクトをローカルの Ivy リポジトリに公開する。updateライブラリ依存性の解決と取得を行う。

コンフィギュレーション・レベルのタスク

コンフィギュレーション・レベルのタスクは、コンフィギュレーションに関連付けされたタスクだ。例えば、compile は Compile/compile と等価であり、(Compile コンフィギュレーションで管理される) main のソースコードをコンパイルする。Test/compile は (Test コンフィギュレーションで管理される) テストのソースコードをコンパイルする。Compile コンフィギュレーションのほとんどのタスクはTest コンフィギュレーション内に対応するものがあり、Test/ とプレフィックスを付けることで実行できる。

-

compile(src/main/scalaディレクトリの中の) main のソースをコンパイルする。Test/compileは、 (src/test/scalaディレクトリの中の) テストのソースをコンパイルする。 -

consoleコンパイルされたソース、libディレクトリ内の全ての JAR、マネージ依存性を含んだクラスパスを用いて Scala インタプリタを起動する。sbt へ戻るには、:quit、Ctrl+D (Unix)、もしくは Ctrl+Z (Windows) と打ち込む。同様に、Test/consoleはテストクラスとクラスパスを用いてインタプリタを起動する。 -

docscaladoc を用いてsrc/main/scala/内の Scala ソースの API ドキュメンテーションを生成する。Test/docは、src/test/scala内のソースファイルのための API ドキュメンテーションを生成する。 -

packagesrc/main/resources内のファイルとsrc/main/scalaからコンパイルされたクラスを含む JAR ファイルを作成する。Test/packageは、src/test/resources内のファイルとsrc/test/scalaからコンパイルされたクラスを含む JAR ファイルを作成する。 -

packageDocsrc/main/scala内の Scala ソースより生成された API ドキュメンテーションを含む JAR ファイルを作成する。Test/packageDocは、src/test/scala内のテスト・ソースより生成された API ドキュメンテーションを含む JAR ファイルを作成する。 -

packageSrc全ての main のソースファイルとリソースを含む JAR ファイルを作成する。パッケージはsrc/main/scalaおよびsrc/main/resourcesからの相対パスとなる。同様に、Test/packageSrcはテストソースとリソースをパッケージ化する。 -

run <引数>*サブプロジェクトのメインクラスを sbt と同じ JVM 上から実行する。引数はそのままメインクラスに渡される。 -

runMain <メインクラス> <引数>*サブプロジェクトから指定されたメインクラスを sbt と同じ JVM 上から実行する。引数はそのままメインクラスに渡される。 -

test <test>*引数で指定されたテスト (省略された場合は全てのテスト) を以下の条件で実行する:- 未だ実行されていない、もしくは

- 前回実行されたときに失敗した、もしくは

- 前に成功してから間接的依存性のいずれかが再コンパイルされた

*は、テスト名のワイルドカードとして解釈される。

-

testFullテストのコンパイル時に検知された全てのテストを実行する。

一般コマンド

shutdownsbt server をシャットダウンして現行の sbt セッションを終了する。exitorquitEnd the current interactive session or build. Additionally, Ctrl+D (Unix) or Ctrl+Z (Windows) will exit the interactive prompt.help <command>Displays detailed help for the specified command. If the command does not exist, help lists detailed help for commands whose name or description match the argument, which is interpreted as a regular expression. If no command is provided, displays brief descriptions of the main commands. Related commands are tasks and settings.projects [add|remove <URI>]List all available projects if no arguments provided or adds/removes the build at the provided URI.

-

Watch command

~ <command>Executes the project specified action or method whenever source files change. -

< filenameExecutes the commands in the given file. Each command should be on its own line. Empty lines and lines beginning with '#' are ignored -

A ; BExecute A and if it succeeds, run B. Note that the leading semicolon is required. -

eval <Scala-expression>Evaluates the given Scala expression and returns the result and inferred type. This can be used to set system properties, as a calculator, to fork processes, etc ... For example:> eval System.setProperty("demo", "true") > eval 1+1 > eval "ls -l" !

Commands for managing the build definition

-

reload [plugins|return]If no argument is specified, reloads the build, recompiling any build or plugin definitions as necessary. reload plugins changes the current project to the build definition project (inproject/). This can be useful to directly manipulate the build definition. For example, running clean on the build definition project will force snapshots to be updated and the build definition to be recompiled. reload return changes back to the main project. -

set <setting-expression>Evaluates and applies the given setting definition. The setting applies until sbt is restarted, the build is reloaded, or the setting is overridden by another set command or removed by the session command. -

session <command>Manages session settings defined by thesetcommand. It can persist settings configured at the prompt. -

inspect <setting-key>Displays information about settings, such as the value, description, defining scope, dependencies, delegation chain, and related settings.

sbt runner and launcher

When launching the sbt runner from the system shell, various system properties or JVM extra options can be specified to influence its behaviour.

sbt JVM options and system properties

If the JAVA_OPTS and/or SBT_OPTS environment variables are defined when sbt starts, their content is passed as command line arguments to the JVM running sbt server.

If a file named .jvmopts exists in the current directory, its content is appended to JAVA_OPTS at sbt startup. Similarly, if .sbtopts and/or /etc/sbt/sbtopts exist, their content is appended to SBT_OPTS. The default value of JAVA_OPTS is -Dfile.encoding=UTF8.

You can also specify JVM system properties and command line options directly as sbt arguments: any -Dkey=val argument will be passed as-is to the JVM, and any -J-Xfoo will be passed as -Xfoo.

See also sbt --help for more details.

sbt JVM heap, permgen, and stack sizes

If you find yourself running out of permgen space or your workstation is low on memory, adjust the JVM configuration as you would for any java application.

For example a common set of memory-related options is:

export SBT_OPTS="-Xmx2048M -Xss2M"

sbt

Or if you prefer to specify them just for this session:

sbt -J-Xmx2048M -J-Xss2M

Boot directory

sbt runner is just a bootstrap, the actual sbt server, Scala compiler and standard library are by default downloaded to the shared directory \$HOME/.sbt/boot/.

To change the location of this directory, set the sbt.boot.directory system property. A relative path will be resolved against the current working directory, which can be useful if you want to avoid sharing the boot directory between projects. For example, the following uses the pre-0.11 style of putting the boot directory in project/boot/:

sbt -Dsbt.boot.directory=project/boot/

Terminal encoding

The character encoding used by your terminal may differ from Java's default encoding for your platform. In this case, you will need to specify the file.encoding=<encoding> system property, which might look like:

export JAVA_OPTS="-Dfile.encoding=Cp1252"

sbt

HTTP/HTTPS/FTP Proxy

On Unix, sbt will pick up any HTTP, HTTPS, or FTP proxy settings from the standard http_proxy, https_proxy, and ftp_proxy environment variables. If you are behind a proxy requiring authentication, you need to pass some supplementary flags at sbt startup. See JVM networking system properties for more details.

For example:

sbt -Dhttp.proxyUser=username -Dhttp.proxyPassword=mypassword

On Windows, your script should set properties for proxy host, port, and if applicable, username and password. For example, for HTTP:

sbt -Dhttp.proxyHost=myproxy -Dhttp.proxyPort=8080 -Dhttp.proxyUser=username -Dhttp.proxyPassword=mypassword

Replace http with https or ftp in the above command line to configure HTTPS or FTP.

Other system properties

The following system properties can also be passed to sbt runner:

-Dsbt.banner=true

Show a welcome banner advertising new features.

-Dsbt.ci=true

Default false (unless then env var BUILD_NUMBER is set). For continuous integration environments. Suppress supershell and color.

-Dsbt.client=true

Run the sbt client.

-Dsbt.color=auto

- To turn on color, use

alwaysortrue. - To turn off color, use

neverorfalse. - To use color if the output is a terminal (not a pipe) that supports color, use

auto.

-Dsbt.coursier.home=$HOME/.cache/coursier/v1

Location of the Coursier artifact cache, where the default is defined by Coursier cache resolution logic. You can verify the value with the command csrCacheDirectory.

-Dsbt.genbuildprops=true

Generate build.properties if missing. If unset, this defers to sbt.skip.version.write.

-Dsbt.global.base=$HOME/.sbt/

The directory containing global settings and plugins.

-Dsbt.override.build.repos=true

If true, repositories configured in a build definition are ignored and the repositories configured for the launcher are used instead.

-Dsbt.repository.config=$HOME/.sbt/repositories

A file containing the repositories to use for the launcher. The format is the same as a [repositories] section for a sbt launcher configuration file. This setting is typically used in conjunction with setting sbt.override.build.repos to true.

sbt update

See library depdency basics in the Getting Started guide to learn about the basics.

書式

sbt [query / ] update

説明

sbt uses Coursier to implement library management, also known as a package manager in other ecosystems. The general idea of library management is that you can specify external libraries you would like to use in your subprojects, and the library management system would:

- Check if such versions exists in the listed repositories

- Look for the transitive dependencies (i.e. the libraries used by the libraries)

- Attempt to resolve version conflicts, if any

- Download the artifacts, such as JAR files, from the repositories

Dependencies

Declaring a dependency looks like:

libraryDependencies += groupID %% artifactID % revision

or

libraryDependencies += groupID %% artifactID % revision % configuration

Also, several dependencies can be declared together:

libraryDependencies ++= Seq(

groupID %% artifactID % revision,

groupID %% otherID % otherRevision

)

If you are using a dependency that was built with sbt, double the first % to be %%:

libraryDependencies += groupID %% artifactID % revision

This will use the right JAR for the dependency built with the version of Scala that you are currently using. If you get an error while resolving this kind of dependency, that dependency probably wasn't published for the version of Scala you are using. See Cross building for details.

versionScheme and eviction errors

sbt allows library authors to declare the version semantics using the versionScheme setting:

// Semantic Versioning applied to 0.x, as well as 1.x, 2.x, etc

versionScheme := Some(VersionScheme.EarlySemVer)

When Coursier finds multiple versions of a library, for example Cats Effect 2.x and Cats Effect 3.0.0-M4, it often resolves the conflict by removing the older version from the graph. This process is colloquially called eviction, like "Cats Effect 2.2.0 was evicted."

This would work if the new tenant is binary compatible with Cats Effect 2.2.0. In this case, the library authors have declared that they are not binary compatible, so the eviction was actually unsafe. An unsafe eviction would cause runtime issues such as ClassNotFoundException. Instead Coursier should've failed to resolve.

lazy val use = project

.settings(

name := "use",

libraryDependencies ++= Seq(

"org.http4s" %% "http4s-blaze-server" % "0.21.11",

"org.typelevel" %% "cats-effect" % "3.0.0-M4",

),

)

sbt performs this secondary compatibility check after Coursier returns a candidate:

[error] stack trace is suppressed; run last use / update for the full output

[error] (use / update) found version conflict(s) in library dependencies; some are suspected to be binary incompatible:

[error]

[error] * org.typelevel:cats-effect_2.12:3.0.0-M4 (early-semver) is selected over {2.2.0, 2.0.0, 2.0.0, 2.2.0}

[error] +- use:use_2.12:0.1.0-SNAPSHOT (depends on 3.0.0-M4)

[error] +- org.http4s:http4s-core_2.12:0.21.11 (depends on 2.2.0)

[error] +- io.chrisdavenport:vault_2.12:2.0.0 (depends on 2.0.0)

[error] +- io.chrisdavenport:unique_2.12:2.0.0 (depends on 2.0.0)

[error] +- co.fs2:fs2-core_2.12:2.4.5 (depends on 2.2.0)

[error]

[error]

[error] this can be overridden using libraryDependencySchemes or evictionErrorLevel

This mechanism is called the eviction error.

Opting out of the the eviction error

If the library authors have declared the compatibility breakage, but if you want to ignore the strict check (often for scala-xml), you can write this in project/plugins.sbt and build.sbt:

libraryDependencySchemes += "org.scala-lang.modules" %% "scala-xml" % VersionScheme.Always

To ignore all eviction errors:

evictionErrorLevel := Level.Info

Resolvers

sbt uses the standard Maven Central repository by default. Declare additional repositories with the form:

resolvers += name at location

For example:

libraryDependencies ++= Seq(

"org.apache.derby" % "derby" % "10.4.1.3",

"org.specs" % "specs" % "1.6.1"

)

resolvers += "Sonatype OSS Snapshots" at "https://oss.sonatype.org/content/repositories/snapshots"

sbt can search your local Maven repository if you add it as a repository:

resolvers += Resolver.mavenLocal

Override default resolvers

resolvers configures additional, inline user resolvers. By default, sbt combines these resolvers with default repositories (Maven Central and the local Ivy repository) to form externalResolvers. To have more control over repositories, set externalResolvers directly. To only specify repositories in addition to the usual defaults, configure resolvers.

For example, to use the Sonatype OSS Snapshots repository in addition to the default repositories,

resolvers += "Sonatype OSS Snapshots" at "https://oss.sonatype.org/content/repositories/snapshots"

To use the local repository, but not the Maven Central repository:

externalResolvers := Resolver.combineDefaultResolvers(resolvers.value.toVector, mavenCentral = false)

Override all resolvers for all builds

The repositories used to retrieve sbt, Scala, plugins, and application dependencies can be configured globally and declared to override the resolvers configured in a build or plugin definition. There are two parts:

- Define the repositories used by the launcher.

- Specify that these repositories should override those in build definitions.

The repositories used by the launcher can be overridden by defining ~/.sbt/repositories, which must contain a [repositories] section with the same format as the Launcher configuration file. For example:

[repositories]

local

my-maven-repo: https://example.org/repo

my-ivy-repo: https://example.org/ivy-repo/, [organization]/[module]/[revision]/[type]s/[artifact](-[classifier]).[ext]

A different location for the repositories file may be specified by the sbt.repository.config system property in the sbt startup script. The final step is to set sbt.override.build.repos to true to use these repositories for dependency resolution and retrieval.

Exclude Transitive Dependencies

In certain cases a transitive dependency should be excluded from all dependencies. This can be achieved by setting up ExclusionRules in excludeDependencies.

excludeDependencies ++= Seq(

// commons-logging is replaced by jcl-over-slf4j

ExclusionRule("commons-logging", "commons-logging")

)

To exclude certain transitive dependencies of a dependency, use the excludeAll or exclude methods. The exclude method should be used when a pom will be published for the project. It requires the organization and module name to exclude. For example,

libraryDependencies +=

("log4j" % "log4j" % "1.2.15").exclude("javax.jms", "jms")

Explicit URL

If your project requires a dependency that is not present in a repository, a direct URL to its jar can be specified as follows:

libraryDependencies += "slinky" % "slinky" % "2.1" from "https://slinky2.googlecode.com/svn/artifacts/2.1/slinky.jar"

The URL is only used as a fallback if the dependency cannot be found through the configured repositories. Also, the explicit URL is not included in published metadata (that is, the pom or ivy.xml).

Disable Transitivity

By default, these declarations fetch all project dependencies, transitively. In some instances, you may find that the dependencies listed for a project aren't necessary for it to build. Projects using the Felix OSGI framework, for instance, only explicitly require its main jar to compile and run. Avoid fetching artifact dependencies with either intransitive() or notTransitive(), as in this example:

libraryDependencies += ("org.apache.felix" % "org.apache.felix.framework" % "1.8.0").intransitive()

Classifiers